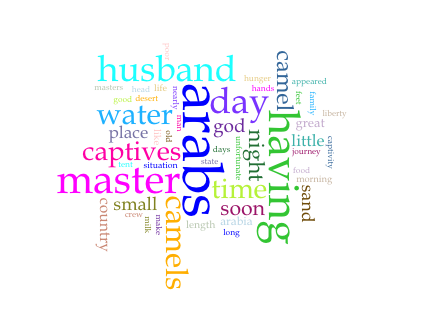

In 1828, a “Travel’g Museum of Fine Arts” advertised its arrival in Hagerstown, Maryland. The ad, appearing in the January 17th issue of the Torch Light, listed some of the “wax figures” featured in its exhibit, including George Washington, Andrew Jackson, the emperor Napoleon, the empress Maria Theresa, Simon Bolivar, Joan of Arc, and then-U.S. President John Quincy Adams (see image). Also included was the figure of “Mrs. ELIZA BRADLEY, who was taken prisoner by the Arabs on the coast of Arabia.” Bradley was the subject and putative author of a Barbary captivity narrative first published in 1820. The popularity of her story is attested to by her appearance in wax alongside illustrious historical figures as well as a few well-known fictional characters (like Charlotte Temple and Lady Helen Mar) whom many believed to be real. Bradley, it turns out, was among the latter, but her fictional story drew, at least in part, from real experiences of shipwreck and captivity by North African pirates. Our introduction to this critical edition of her narrative situates this fascinating text in the contexts of cultural, political, religious, literary, and book history.

When An Authentic Narrative of the Shipwreck and Sufferings of Mrs. Eliza Bradley was published in 1820, a wide range of information both informed and influenced readers’ perception of, interpretation of, and interaction with the narrative. Piracy, as well as tales of captivity, were topics of constant discussion and observation in early nineteenth-century America. To understand the complexity of piracy off the North African coast during this period, and how Americans viewed it, we must understand the term “pirate” and all that it encompasses. There are many differences across regional definitions of piracy, which leads to discrepancies in policies and laws against the practice. As a general blanket statement, one can assume that piracy thrives on poor socioeconomic conditions of a state, government, and community. These conditions applied to the Middle East and North Africa during the beginning of the nineteenth century, but there are more elements that play into the fostering of piracy off of North African coasts. As Anshul Jain explains in his article on the economic complexity of North Africa, there must be a “minimal level of basic governance” in order for piracy to thrive, “as pirates require access to basic economic outlets.” The economic and political climate of North Africa heavily influenced the prevalence of piracy and the ensuing practices of captivity, slavery, and acts of ransom.

Piracy has been prevalent along the coast of North Africa (otherwise known as the Barbary Coast) for centuries. Initially, in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, pirates only attacked the coastal populations as well as Spanish ships. However, as they grew increasingly powerful and violent in the seventeenth, eighteenth, and nineteenth centuries as a result of backing and support from the Ottoman Empire, African pirates attacked all trading vessels no matter what nationality or where they came from. Christian Europeans, during these centuries, were taken captive by the tens of thousands. The trade in European slaves was so prevalent that between 1520 and 1830, “an average of 2,000-3,000 slaves were sold each year,” making it one of the most profitable trades in North Africa. Europeans “feared captivity in Barbary as though it were death” (Wheelan 21). As soon as a ship was captured by a band of Barbary pirates, crewmembers’ clothes were taken and replaced with rags, they were stripped of their right to constant food and water, and they were put in shackles and made to work hard labor on ships or sent to a slave market (though the prettiest and strongest were chosen to either be gifts or be sent to a palace).

By the turn of the nineteenth century the North African kingdoms were a well known thorn in the side of European naval trade. These kingdoms, which had grown powerful as members of various Islamic Caliphates, had by the time of the Bradley narrative, become weak compared to Europe’s great powers. The North African kingdoms, while vast, were without the resources of many other nations. Furthermore, the majority of their population consisted of nomadic tribal groups warring with each other. These tribal groups were both difficult to rule and difficult to tax. As a result, those in power in these kingdoms required an external source of revenue. Without the industry or resources for favorable trade, these kingdoms turned towards raiding for their survival. One of the most lucrative forms of this raiding was the capture and subsequent ransom of Europeans.

In the early years of this policy, beginning around the year 1600 (Lane-Poole), North Africans attacked Mediterranean merchant vessels, and even went so far as to raid coastal settlements. In those days this was a significant problem for Europeans, and the practice created a lasting animosity (Rejeb). Europe had a long history of weakness when attempting to face the issue of piracy and captured ships. This weakness included payments of ransom and tribute, which in turn fostered the pirates’ motivation to continue capturing ships. Europe paid more and more to have their captives return home or to have safe transit in the oceans (Turner). However, as European nations grew more powerful both through colonial conquests and the degradation of the many Islamic nations, raiding Europeans became a much less tempting prospect for the North Africans. By the birth of the American nation, these African kingdoms were sorely in need of a weaker power to attack. You can imagine how attractive, then, a newly-independent America looked to the Barbary pirates in the years after the Revolutionary War.

In the years following the Revolutionary War, America as a nation was struggling to define itself. As a fledgling nation the prevailing sentiment was in line with the tone of George Washington’s farewell address in which he counselled the nation to avoid foreign entanglements and to stay out of European politics. While the United States sought to remain independent from Old World powers, actors within the new economy were dependent on foreign trade. President Jefferson, elected in 1801, believed in a United States composed of yeomen farmers devoted to their own self sufficiency. Despite this, trade vessels under an American flag and carrying American citizens traveled across the Atlantic regularly. These merchants and sailors traveled to bring wealth to themselves and their new nation, but they also represented a distinct vulnerability. America may have defeated Britain, but free from British dominion the nation was without the military, and most importantly naval, might to compete on a world stage.

A turning point came in October 1784 when an American merchant ship was captured by Barbary pirates. The crew of eleven was taken hostage in Morocco. As a result of the United States lacking both a significant naval force to prevent these seizures, as well as funding to provide for a Navy, the “Continental Congress ultimately decided to follow the European lead and authorized $80,000 to ‘negotiate peace’ with Morocco to obtain the release of the prisoners” (Turner). This began to incentivize Barbary pirates, and not only two weeks later did two more American ships get captured; a total of 21 hostages. In 1796, the United States signed a peace treaty with Algiers. Unfortunately, it then became well known that the United States was willing to pay for peace across the North African coast. As a result, other Barbary states made threats towards American ships unless they were paid generously and quickly.

American merchant vessels quickly became a prized target for North African corsairs. As difficult as it was for the American nation to find the wealth for the ransoms demanded for their people, America did not have the naval power to contend with the North Africans. Following the doctrine established by Thomas Jefferson, and as a result of the wishes and views of George Washington and other founding fathers, what Navy the United States had was devoted to defending its own shores. Primarily this Navy was comprised of small quick vessels which could patrol the American coast. Such ships, as was shown in the war of 1812, were no match for European warships. When Americans were taken prisoner there was little the United States could do to secure their release. However, unlike other nations, the United States was not as willing to pay the ransom for its lost people. This resulted in many Americans remaining in slavery in North African kingdoms. While private efforts were made to secure these prisoners’ release, without the official action of the government, such efforts returned mixed results.

While the majority of North African states were antagonistic towards the interests and people of the United States, the nation of Morocco was quite friendly. Following the beginning of the American Revolution, Morocco (where most of Bradley’s narrative takes place) was the first foreign nation to recognize American independence. As a result of the increasing conflict between North African nations and European great powers, some sought an ally against these great powers. The same forces which made United States merchant shipping a target also framed the nation as an attractive ally. Morocco’s decision to greet the new nation on friendly terms meant that it could not attack U.S. shipping, but it also gave them a potentially powerful ally against European interest. Furthermore, aiding the United States allowed Morocco to take action towards weakening the British Empire. As a result of this friendly status American naval vessels were able to take shelter and resupply within the ports of Morocco, and Morocco became a de facto conduit for the U.S.’s political interests within North Africa. Thus it is not surprising that Bradley’s eventual release from captivity is found within a Moroccan city. Though the narrative portrays Bradley as a British subject, an American audience would be more likely to view Morocco as friendly. In addition to Morocco being characterized as a more amiable nation within North Africa, the overall context of the Bradley narrative would have been consistent with the political realities at the time of the narrative’s publication. The U.S., while gaining in its ability to project power, was still primarily a seclusionist nation at this time. Questions of how the U.S. should see itself in relation to world politics were still being hotly debated. Furthermore, at the time of the narrative, despite having little chance of becoming a peer to the great powers of the time, the nation was attempting to define itself among the weaker powers. The North African states, with their attacks on American interests, were the most direct threat to America’s perceived power (Kilmeade and Yaeger). As a result Americans were very interested in the nature of the North African kingdoms and people. Furthermore, after centuries of narratives which characterized North Africa as villainous, Americans were primed to continue this belief. The Bradley narrative’s story is consistent with American perceptions of themselves, as portrayed by Europeans, as well as with portrayal of North Africans. It is quite possible that the success of the narrative is owed in part to the anxieties of the time.

As these political changes took place, the important religious movement known as the Second Great Awakening occurred in the early nineteenth century. This religious revival swept through the United States like a wildfire, and led to many changes in religious practice. In the wake of the religious movement, new denominations were formed and Christianity was spread throughout the states. With renewed vigor in their beliefs, Christians became more active in their missionary work and felt an increased need to spread the word of the Bible to foreign nations.

In her narrative, Eliza Bradley becomes a missionary in her own right as she shares the Bible with her fellow captives during her journey. Women were the primary converts during the Second Great Awakening and were seen as responsible for passing on their beliefs to others and the next generation. Several women preachers have been documented during the era that the narrative was written, emphasizing its importance for other women who may have become lax in their beliefs or who did not have the confidence to vocalize what they believed in. In addition to women preachers, there were many female religious writers who produced important documents aimed toward other Christian women. At times when the narrative breaks from the central plot and focuses on the reader’s personal beliefs, Eliza Bradley’s narrative appears to be geared explicitly toward an audience of Christian women.

Along with the ministerial overtones, the narrative also examines the religious practices of Islamics—known as Mahometans or Arabs in the story—and their contrasting beliefs when compared to Christians. It is interesting to note that Western missionaries came to North Africa in the 1700s and their presence became more institutionalized after 1884—precisely when the narrative was published in several editions (Patterson 182). Arabs were seen as the “other” by many Christians and were considered barbarous and primitive. The word Arab in the text is in fact a misnomer since many Christians during the time did not understand the nuances of the Islamic religion and the true divisions between different Islamic peoples. Many Barbary captivity narratives written during the same time period as the Bradley narrative made “distinctions between Turks and Bedouins, as well as between Arabs and Moors,” based on what little understanding they had of the foreign culture (Berman 9). The distinctions made between ethnicities, as Jacob Rama Berman points out, “are significant not only because they speak to the creation of American racial maps but also because the first group of actual Arab immigrants to America were predominantly Christian” (9-10).

The theme of religion can clearly be seen through the Bradley narrative, with its female captive depending on the Holy Bible for strength and guidance. While some of the most popular Barbary captivity narratives featured female captives, there are no historically authentic stories written by American women (Baepler 10). In fact, Robin Miskolcze confirms that “no female British or American woman was ever held in captivity by any of the Barbary states in the nineteenth century” (107). This historical information is one source of evidence to indicate that Eliza Bradley’s narrative is a work of fiction rather than a factual account. According to the critic Keith Huntress, preceding shipwreck and captivity narratives, such as the accounts of Captain James Riley and Maria Martin, provided a source of inspiration, plagiarism, and success that led to the production of Eliza Bradley’s narrative (9). While James Riley’s narrative was a true account, Maria Martin’s account was an early work of fiction (Huntress 8). Martin’s History of the Captivity and Sufferings of Mrs. Maria Martin Who Was Six Years a Slave in Algiers: Two of Which She Was Confined in a Dark and Dismal Dungeon, Loaded with Irons, for Refusing to Comply with the Brutal Request of a Turkish Officer, was published in 1807, followed by Bradley’s An Authentic Narrative of the Shipwreck and Sufferings of Mrs. Eliza Bradley in 1820. Incidentally, both of these female captivity accounts were extremely popular with American audiences, despite the fact that both female heroines were not even American. Although Martin and Bradley claimed to be Englishwomen, there is no proof of any original English edition of either of their books, which seems to confirm the fictional nature of both accounts (Huntress 7). But if both female heroines were not American, then why did these female captivity narratives attract so much interest in America?

According to Miskolcze, the very reason why these female captivity narratives gained interest in America was because the shipwrecked female captives were not American (100). The way of thinking and code of morality code prescribed by these Englishwomen was relatable to Americans, which allowed for “Americans to conflate ‘Englishness’ and ‘Americanness’ into an Anglo-American identity” (Miskolcze 100). This merging of English and American national ideals justified Anglo-American racial superiority, placing the Barbary states in the role of the distinct “Other” (Miskolcze 100). Thus, these female Barbary captivity narratives both reflected and dictated Anglo-American ideas of race, culture, and politics. Miskolcze suggests that, in part, the popularity of these narratives was due to the message that these narratives portrayed of the connection between the English and Americans and their shared imperialistic goal of civilizing North Africans (115).

However, as no female captive was ever taken by any of the Barbary states, the question remains: why were these captives portrayed as female heroines? Another part of these books’ popularity could be attributed to the fact that the stories featured women rather than men. But what could a female heroine achieve that a male hero could not? While both men’s and women’s stories could be terrifying, an account from the female point of view “carried a kind of modern-day tabloid appeal owing to the unlikely but titillating possibilities they posed” (Miskolcze 108). Baepler speculates that if any female captives were captured by Barbary states, it is almost certain that they would be “made into concubines, or subjected to domestic services, unless a considerable ransom is expected for them” (11). The racial and sexual boundaries presented by an Anglo-American female captive allowed for increased audience interest.

Despite the fact that a white female captive would have most likely been subjected to sexual violation, both Martin’s and Bradley’s narratives completely avoid this. Bradley is never subjected to any hint of sexual harassment from her Barbary master while Martin refuses her Turkish officer’s request to be his concubine and is imprisoned in chains. Thus, in both accounts, the female heroines are depicted as respectable women who do not violate any of their moral values. Their stories begin in much the same way, with Martin saying that she is English and born “of respectable and wealthy parents” and Bradley saying she was born in Liverpool, England to “creditable parents.” Both women marry ship captains and accompany their husbands on a trip, which is cut short due to a storm that shipwrecks them into Barbary territory. In this way, Martin and Bradley share certain characteristics as female captives that are also typical of the characteristics that Richard Slotkin, quoted in Miskolcze, attributes to the American captivity narrative. Both female heroines are respectable and middle-class, which is “a common gesture of identification in captivity narratives,” allowing for self-identification with Anglo-American readers (Miskolcze 105). In addition, both characters resist what Slotkin refers to as “the temptation of Indian marriage” and both women are later rescued and reunited with their husbands (Miskolcze 105).

The very first Barbary captivity narrative from America was the story of Joshua Gee’s captivity in Algiers (Baepler 1). Although he was captured in 1680, his narrative was not printed until 1943, and the genre of Barbary captivity actually flourished in America between those dates, largely during the early nineteenth century (Baepler 2) when they caught the attention of antebellum America. While An Authentic Narrative of the Shipwreck and Sufferings of Mrs. Eliza Bradley was widely read and hugely popular during its time, it was actually overshadowed by the much more influential and enduring Authentic Narrative of the Loss of the American Brig Commerce (1817) by Capt. James Riley. At the height of the genre’s popularity, James Riley’s tale of enslavement in North Africa made him a household name. Such Barbary captivity narratives were for many Americans a first view of the world outside of Western civilization. Since this genre became such a phenomenon at such an integral point in American history, we might ask what influence it had on racial formation in antebellum America. At this point in America’s history, race and nationality were no longer indicative of one another. For many Americans, race became simplified to black versus white. Under such circumstances, how did Barbary captivity narratives inform American perspectives on slavery in the decades before the Civil War?

One could argue that Barbary captivity narratives were one of the most prominent popular cultural artifacts to shape how Americans viewed slavery. According to Paul Baepler, as a young man Abraham Lincoln owned a copy of James Riley’s Authentic Narrative of the Loss of the American Brig Commerce and considered it among the most influential books on his ideology (217-218). Barbary captivity narratives positioned the reader to understand the horrors and inhumanities of slavery by allowing them to put themselves in the shoes of enslaved European and American protagonists.

While many cite Barbary captivity narratives as a huge turning point for how Americans considered the morality of slavery, others interpreted these texts in a very different manner. Since Barbary captivity narratives were also many Americans’ first introduction to North African and Arab culture, their readers often came to understand Arabs as monstrous barbarians terrorizing their white victims. This depiction caused readers to take these exaggerated depictions at face value and consider those racial identities as inferior to their own. The narratives’ depictions of non-white characters as the antagonists of the genre became hugely influential in developing perceptions of exoticism, otherness, and most significantly racial categorization. Essentially Barbary captivity narratives could be interpreted as either evidence of the evils of slavery and the need for abolition, or as proof of the moral inferiority of non-white persons and thus justification for their enslavement.

Riley’s Authentic Narrative of the Loss of the American Brig Commerce has been universally considered an abolitionist text. Despite the fact that the narrative portrays Arabs and North Africans in a generally unfavorable light, as barbarians, the main conclusion of the narrative is that the institution of slavery is horrible. An Authentic Narrative of the Loss of the American Brig Commerce exoticizes and otherizes Arabs even as it conveys the horrors of slavery. Keith Huntress has pointed out that multiple pages in Bradley’s Authentic Narrative are directly copied, and many more may be indirectly borrowed, from Riley’s Sufferings in Africa. Given this indebtedness to the Riley, we need to ask what purpose the Bradley narrative serves and whether it follows or departs from the purpose of the Riley? This question is best answered by considering how formative Barbary captivity narratives were in shaping people’s views on slavery, and especially by taking into account how influential the Riley narrative was in terms of spreading abolitionist sentiment. One could conclude that the Bradley narrative is a reframing of the Riley narrative to appeal to a pro-slavery, anti-abolitionist reading demographic.One significant difference between the Bradley and Riley is the former’s reliance on Christianity and religious devotion to otherize the Muslim antagonists of the story. Bradley throughout the narrative proclaims her devotion to Christianity and condemns her Muslim captors as heathens. Exacerbating religious difference was a common way to dehumanize non-white persons to readers. In fact, stories of Barbary captivity were sometimes disseminated through religious sermons. For example, Cotton Mather, a prominent Puritan minister, proclaimed the evil of the heathens from North Africa. In a sermon, he referred to the captors in these narratives as “Hellish pirates” and “barbarous negroes” (Mather, in Baepler, 219). This rhetoric increased the divide between Christians and non-Christians, and one can see this division mirrored in how the Bradley text implements Christian scripture and terminology.

The most prominent divergence between the framing of the two narratives is that Bradley’s story is told from the point of view of a white woman. White female bodies have often been weaponized for the sake of protecting society at large. This white-patriarchal view suggests that white women must be protected at all costs from the violence of non-white persons (Wolfe). The corruption of white female bodies would appear to lead to the corruption of society, since those bodies are meant to be a symbol of purity and non-corruption. In this instance, the fact that Bradley’s white body is under threat by North African Muslims reinforces the imperative to protect white female bodies from the prejudicial threat of non-white male ones. This framework would have created a visceral emotional reaction to Bradley’s plight, and especially against her captors. It immediately causes the reader to consider how significantly race plays a part in how Bradley’s captors treat her.

In many Barbary captivity narratives, the narrator participates in the culture of imperialism by using rhetoric that differentiates the captive’s Western culture from the captor’s non-Western culture and subjugates the latter to Western bias. Moral and cultural superiority could be established through descriptions of the characters and governments of the captors. An in-depth reading of Bradley’s narrative determines that, between the extremes of objectifying and portraying her captors as foils for her idealized Christian character on the one hand, and wholly sympathizing with them and praising their practices on this other, this particular female-led narrative falls in the middle. While Bradley repeatedly uses the words “merciless” to describe the actions of the Arab tradesmen, multiple examples of “humanizing” descriptions occur when she negotiates with her captors, speaking to their reasoning and ability to show tenderness. Though it is common for American captivity narratives to take after their British predecessors in casting non-Christian practices of worship as inferior, the Bradley narrative contains rhetoric that cancels out religious imperialistic notions.

These moments are significant because depictions of Africans as noble or exemplary are infrequent in American Barbary captivity narratives. As Stephen Wolfe argues, the bodies of the captives in American Barbary Coast narratives are significant signs of the political and social arguments for blurring racial boundaries at the time of publishing (8). They serve as interesting place-markers for attitudes toward national and socio-political identity throughout history. When the bodies are abused and traumatized by abuse from the captors, a story of dehumanization and a construction of barbarity provide rhetorical bearing for anti-slavery activism in the U.S., as well as demonstrating the danger of uncentralized social structure.

When the American travelers cross geographical borders, they also cross “national and racial, cultural and religious” borders (Wolfe 7). These mini-narratives would have been particularly interesting for British and American audiences at a time when, as Nussbaum explains, “there was an appetite for consuming Africa” (74). Not only were the stories a thrill to consume and a way to engage in fantasy, they were also a way to both reinforce and challenge notions of superiority in political structure. After crossing boundaries and being taken captive, American sailors would suffer from burned, darkened skin, which can be read as a “contact zone” marking racial difference. Being stripped of their clothing, the captives lose a sense of identity and community. Exposed to the new harsh environment, their racial identities are at stake as well. No longer are they protected by the privilege of white skin. In Riley’s 1817 An Authentic Narrative of the loss of the American Brig Commerce, for instance, he wonders if his whiteness may be only skin deep (Riley 241, 244-45; Wolfe 15).

According to Wolfe, another change of the body that carries significant meaning for identity is the parching of the tongues of the captors. Being thirsty, they are too tired to speak. Thus, they lose their voice, their language, a source of power and identity and community. In contrast, Bradley’s status as a woman offers her privileges denied to all the other male captives. While the others must walk with the pack, receiving blisters and gashes on their feet, she is given a camel to ride on. Because female captives are more precious than male captives, her master prefers that she sleep in the tent, while the other slaves remain outside. Under less physical strain, social structure shifts such that she ministers to them, encouraging them to pray and reading verses to them from her Bible. Her voice gains power in this foreign land.

Captivity narratives were not exempt from acting as fictionalized propaganda that favored British government over the despotisms of the other culture, as well as Protestant over Catholic religious identity. Joe Snader explains that it was during and after the war for American independence that “the target of propaganda shifted from the French to the British” (65) as competition for American territorial expansion coincide with narratives that hint at the “tyrannical” institutions of southern Europe (66). Shortly after winning independence, American publishers put out narratives that helped show the contrast between “liberty and tyranny, Britain and Southern Europe, Protestantism and Catholicism” (Snader 71). As seen in the Bradley narrative, the religious practices of her Arab captors as she documented them provided a foil for her Protestant Christianity as she praised the supplication of a God that would deliver her, as opposed to keeping her captive. There are also moments in the Bradley narrative where she emphasizes the importance of property to the Arabs, which might contrast with the apparent democracy and simplicity of the American system that emphasizes one God, one free people. The extremes that this genre undertakes range from “virulently racist propaganda” to “deeply troubled accounts of extensive transculturation” (Snader 62). Yet historically, many early British captive narratives from the 1500s to 1700s blurred the “conceptual boundaries” between Western captives and non-Western captors. Essentially, sometimes the Western cultures were portrayed as the barbarian ones, while the captors’ cultures were made to appear less cruel, even peaceful in contrast. Still, captivity narratives functioned as fictionalized propaganda, especially when incorporated into other literary genres that depicted Christian slaves held captive in Africa. In Susanna Rowson’s play Slaves in Algiers, the superiority of American freedom as a virtue becomes a central theme. In the very first act of the first scene, a slave named Rebecca talks about her longing for freedom, comparing herself to a bird that--despite being treated well--desires liberty above all else. To further undo the notion of a happy and content slave, a scene is painted where the master says to this slave: “I have condescended to request you love me” (1.1). The plot develops as Rebecca delivers agreeable lines about how woman is made equal to man, and it is revealed that she learned these ideals from a woman who is American. In Rebecca’s mind, America is “that land, where virtue in either sex is the only mark of superiority” (1.1). Then there is the villainous Algerian master, named Ben Hassan. The writer gives him an accent and a vernacular with unique grammar structure, and the Algerian culture is denigrated almost immediately as Hassan offers to make Rebecca his wife despite being married: “Ish, but our law gives us great many vives.—our law gives liberty in love; you are an American and you must love liberty” (1.2) As a work of contextualized fiction created to entertain the masses, this play offers insight as to how popular audiences viewed Africans and their values. This play, like Bradley’s narrative, justifies Christianity as the superior religion, one that offers liberty without the licentiousness that other religious cultures do.

When Bradley’s narrative was first published in 1820, it was a transitional time in the publishing industry. For example, copyright laws were in a state of flux between England and America. The Copyright Act of 1790 excluded foreign authors from its copyright laws and almost encouraged American publishers to reprint and blatantly plagiarize foreign books. These conditions fostered the publication of a book like this one, that made numerous pretences to being something other than it actually was. Because of the Copyright Act’s cavalier attitude toward plagiarism, many publishers opposed international copyright laws and instead envisioned what Meredith McGill describes as “a literary marketplace that operated according to republican principles--one in which profiteering could be counteracted by the limitless multiplication of editions, radically expanding the number of individuals who could benefit from the sale of any one text” (75). The “multiplication of editions” can be seen in the multitude of editions of the Bradley narrative that were published during its 28-year span of republication in the nineteenth century, as the book was reprinted and new editions were released between 1820 and 1848. After that it fell out of print, before making a comeback in 1985, when Ye Galleon Press published an edition by Keith Huntress.

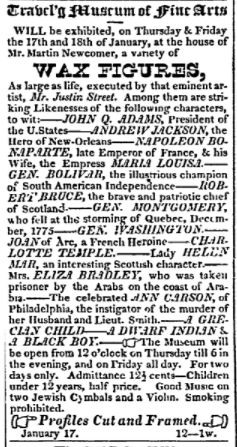

Along with political change, there were also more practical changes occurring in how books were actually produced in the early nineteenth century. The Bradley narrative was bound using a relatively new technique for the time called scaleboarding, which made books cheaper and easier to produce. Scaleboarding became the popular method of binding books at this time. Scaleboarding is a technique that “utilized thin, planed wooden boards” which were “used by printers for justifying” books (Wolcott 59). This method of bookbinding became popular because of the abundance of wood available in America, which also helped to lower the price of books. Books were not sewn together but instead were bound using “stitching or stabbing the text block” (see image above, of one 1820 edition of the Bradley narrative) which “sped the binding process tremendously and likely lowered the price of the finished volume” (Wolcott 61). Scaleboarding allowed for faster and cheaper production of books and helped the expanding publishing industry meet the nineteenth-century demand created by Sunday Schools, changing demographics, and increased literacy throughout America. These facts combined to make it possible for the Bradley narrative to be circulated amongst publishers, which resulted in multiple editions.

Another fact which contributed to the popularity of the Bradley narrative for publication, was its religious tones. Throughout the narrative Mrs. Bradley prays and even preaches to her husband and fellow captives. Mrs. Bradley’s religious teachings fit perfectly into the moral code which governed the book publishing market. In the late eighteenth century it became common practice for markets and businesses to have a sense of “civic humanism,” which helped promote a “godly community” according to scholar Mark Valeri (154). The Bradley narrative supports the godly community because Mrs. Bradley continuously thanks God for the small kindnesses she is afforded during her time in captivity. This way of thinking prevailed into the nineteenth century and was fueled by the growing number of Sunday Schools.

The prominence of Sunday Schools during the nineteenth century may have also been a contributing factor to the popularity of Mrs. Bradley’s story. Schools require books, and religious schools require books with a biblical or theological theme. According to scholar Donald Davis, Sunday schools acquired “curriculum materials, textbooks, religious reference works, popular religious reading, uplifting fiction, drama, poetry, and a smattering of history” (115). The Bradley narrative fits these specifications due to its religious tones and overall happy ending. The demand created by these schools led to “great expansion, perhaps even explosion, of publishing ventures” (Davis 115). While numerous scholars--including Baepler, Huntress, and Bartlett--insist that Bradley’s narrative was used in Sunday schools, we have found no direct evidence to support this claim. The religious ideals perpetuated by Sunday schools, and their rapid growth, may still have contributed to its popularity in some form. Publishers in the early nineteenth century did not just produce books. They also had to distribute their own books. In 1801 the suggestion for a book fair was made as a way to expand the book market, and it was successful for a while. But publishers were still looking for ways to expand their markets. Over the next ten years, book fairs were slowly replaced. Scholar Emily Todd notes that by the 1820s, publishers “had in place a network of booksellers to whom they would send out the newly printed novels” (117). These booksellers would then inform the publishers which books were selling well and which ones remained on the shelves. And due to the multiple printings of the Bradley narrative, it is safe to say that it did quite well among nineteenth century readers.

Nineteenth century readers likely read Eliza Bradley’s narrative as a true account. However, recent research indicates that is a work of fiction with fraudulent foundations. Essentially, shipwreck narratives were hot in the nineteenth century--people craved to read about far off places, the villainous “other,” experience a disastrous event to find it end happily for their European comrade. Before the Bradley text, there existed several similar narratives, some of which achieved a considerable amount of popularity, including the works by Maria Martin and James Riley mentioned above. As described there, the Bradley text borrows heavily from these two books.

The fiction of the Bradley narrative begins even before the story itself, however. In the publisher’s preface specific references are made to two previous printings. The first states, “This publication, having passed through a number of editions in England, and received an uncommon degree of patronage there, being printed almost verbatim from the original manuscript of Mrs. B as the English publisher declares—.” The second reference claims, “The publishers of the European edition, from which this is copied, being acquainted with the family of the writer of this narrative, and the circumstances of the unfortunate voyage upon which it was founded, clearly demonstrates the truth of the occurrences contained in the following pages.” Keith Huntress reports that although the Bradley narrative claims to have “passed through a number of editions,” no English edition of this book is listed in the British Museum Catalogue. The only edition listed in the British Museum was printed in Boston--in 1823. By claiming that another edition preceded this one, the printer (who may also have been the book’s actual author) may be avoiding charges of fraud and plagiarism.

The ghost publisher of the first edition of the Bradley narrative’s thus seems to become much less mysterious. According to Huntress, the first edition “appeared without the name of the publisher on the title page because the publisher did not want to be attributed with plagiarism.” The first edition simply reads “Boston--printed by James Walden--1820.” But then must we ask, who exactly is this James Walden? Wasn’t he worried about being thought responsible for fraudulent behavior? Not exactly. After further investigation into the Catalogue of the American Antiquarian Society, Huntress notes that James Walden is connected to this book, and only this book--“he neither published nor printed any other book.” This leads Huntress to argue that “James Walden” was simply an alias, a made up name used to publish a plagiarized book. Therefore, the responsible party could reap the monetary benefits of a successful shipwreck narrative, yet not worry about any of the consequences.

Though considered absolutely abhorrent behavior in modern-day publishing, the practice of plagiarism was not uncommon in the nineteenth century. According to Laura Langer Cohen, the antebellum era saw immense improvements in technology and the first major “developments in the production and distribution of print” (6). The ability to massively increase printing production destabilized the foundations of American literature. As printing production rose, so did the skepticism surrounding the reliability of the text and its true origins: “Was it a true copy or did it misrepresent the manuscript, intentionally or unintentionally? Did the author named really write it? Was it the kind of text its title purported it to be? Could its contents be trusted?” (Cohen 7). Thus, American literature in the nineteenth century had been likened by its readers to subterfuge, impostures, and plagiarism. Fraudulence became indissociable from American literature--and even definitive of it as readers became hopeless in distinguishing “impostures, forgeries, plagiarisms, and hoaxes from literature proper” (Cohen 2). It was common practice for publishers to “repackage” and republish magazine articles, while writers frequently found their work altered, cut, rearranged, or attributed to others. Due to this fraudulent behavior, a printed text did not inherently mean it was of great importance or stature. Instead, it only ensured that the text remained continually available for adaptation.

During the early half of the century, the Bradley text underwent at least fifteen separate editions from nine different publishers. All nine publishers identify Eliza Bradley herself as the author, furthering this notion that the narrative is a non-fiction, personal account. In 1820, the first editions of the Bradley narrative appeared, one printed (in two different versions that we have found) by James Walden in Boston, Massachusetts, and another by Luther Roby in Concord, New Hampshire. With the exception of the Roby, the first seven editions were all printed in Massachusetts until 1824, when a printer by the name of Abel Brown printed two separate editions in Exeter, New Hampshire in 1824 and 1826. However, all nineteenth-century editions of the text were printed in New England or the wider Northeast--in Massachusetts, New Hampshire, and New York.

Our class meticulously collated the first several pages of eight of these editions available to us at the Santa Clara University Archives and Special Collections. This included two of James Walden’s editions printed in 1820, his 1823 edition, two of George Clark’s 1821 editions, Jonathan Howe’s 1823 edition, J.H. Turney’s 1832 edition, and lastly, Mack Andrus & Woodruff’s 1837 edition. We each sat, one edition per person, reading and following along in our respective edition while one student read aloud from version A of Walden’s 1820 edition. This careful collation allowed us to compare and discuss each disparity--which included, but was not limited to, punctuation, capitalization, format, diction, and aesthetics. Through our collation process, our class discovered seven of the eight editions differed only slightly from each other. The greatest distinction between these seven editions remained the organization and format of the title page. They differed in their font size, spacing, title, and the organization or formatting of paragraphs. Otherwise, the texts have only marginal grammatical differences or small variations in diction. However, one of the editions our class collated does indeed possesses a major difference in respect to the seven other texts. At page 87, version B of the 1820 Walden edition diverges quite considerably from the other seven versions of the narrative and ends with different material than that of the others. Because the language on these pages of version B so closely mimics that of the James Riley narrative, one possibility is that this was the first printed version of the narrative, and that it was rewritten and reorganized slightly to avoid charges of direct plagiarism. A list of known editions of the Bradley narrative appears below.

Concord, MA: Luther Roby, 1820

Boston: James Walden, 1820 - version A

Boston: James Walden, 1820 - version B

Boston: James Walden, 1821

Boston: James Walden, 1823

Boston, George Clark, 1821

Boston: Jonathan Howe 1823

Exeter, NH: Abel Brown, 1824

Exeter, NH: Abel Brown 1826

Concord, MA: L. Roby, 1829.

Boston: John Page, 1832.

Boston: J. Howe, 1832

New York: J. H. Turney, 1832.

Ithaca, NY: Mack, Andrus, & Woodruff, 1835

Ithaca, NY: Mack, Andrus, & Woodruff, 1837

Lowell, MA: H.D. Huntoon, 1848.

--------Fairfield: Washington, Ye Galleon Press, 1985 (edited by Keith Huntress, this edition has chapter breaks added that do not appear in any of the nineteenth-century editions)

Chicago: U of Chicago Press, 1999 (in collection edited by Paul Baepler; the Preface and Appendix on Arabia are left out of this edition)

[Publisher not identified], Nabu Press, 2010 (Worldcat)

We would like to thank the following individuals and institutions for their invaluable assistance in making this edition--and the course in which it was produced--possible. Santa Clara University provided a Teaching with Technology Innovation grant that supported the development of this course, Textual Editing (in Digital Environments). Dr. Natalie Linnell (Computer Science) partnered with Prof. Michelle Burnham (English) to design and teach this interdisciplinary course in digital humanities. Debbie Tahmassebi, Dean of the College of Arts and Sciences, provided support for our experiment in team-teaching. Tom Farrell, Digital Initiatives Librarian, created digitized images of both versions of the James Walden edition of Bradley’s narrative as part of the Library’s Digital Collections. He also introduced us to the mechanics and politics of scanning and OCR, especially for older books. Nadia Nasr, Head of Archives and Special Collections at SCU’s Learning Commons, made the library’s collections and reading room available to us. Elizabeth Newsom, Special Collections librarian, introduced us to the history of early nineteenth-century U.S. book production, purchased multiple nineteenth-century editions of the Bradley narrative, helped guide us through the process of collation, and offered numerous valuable research tips. We thank the members of the Early American Literature listserv (EARAM-L) who fielded our questions, especially Dan E. Williams and Caroline Wigginton. At the University of Michigan’s Clements Library, Emi Hastings, Curator of Books, responded to our questions about Sunday schools and the Bradley narrative. We’re especially grateful to Ashley Cataldo of the American Antiquarian Society for answering numerous questions, sharing images of editions of the Bradley narrative that we did not otherwise have access to, and finding and sharing with us the Torch Light advertisement about the wax museum’s Eliza Bradley figure. We also thank Chris Phillips for putting us in touch with Ashley.

Copyright Santa Clara University, 2017

Copyright Santa Clara University, 2017