History of Print Culture and Books

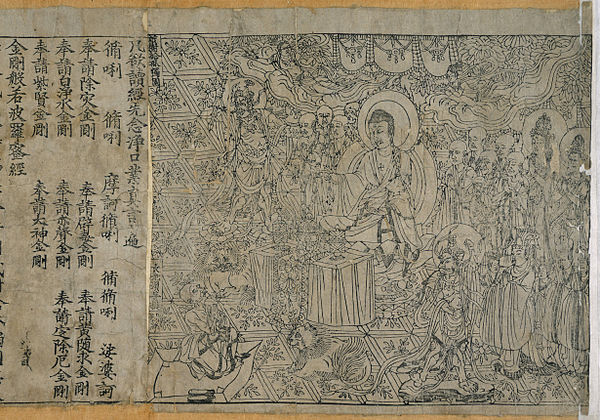

Asia's print culture history, especially in Japan, offers a remarkable account of creativity and adaptation. Prior to the arrival of Chinese script before the fifth century, the ancient Japanese had no written language. This forced the development of distinctive reading and writing systems, such as Kanbun, where Japanese was written wholly in Chinese characters. Japanese writing advanced much further by the end of the eighth century with the development of two phonetic syllabaries known as Kana. Scroll manuscripts introduced during the Asuka period, inscriptions on stone or metal objects, and mokkan (thin wooden tablets) were among the early Japanese texts. Before bound volumes became more frequent during the Edo period, these scrolls which were used for written manuscripts, pictures, and occasionally printed works remained widely used. One of the world's first printing civilizations, printing was brought to Japan during the Nara period via the Korean peninsula. A large quantity of dharani texts were printed on metal plates and sent to temples at the behest of Empress Shōtoku, indicating an early use of printing for religious rather than for reading purposes. Because manuscripts were less expensive to produce than printed works, they continued to be prominent in official and cultural contexts far into the 19th century. Commercial printing began to appear during the Edo period, giving urban audiences access to a broad variety of writings, including modern and classical literature. The bound book and news broadsides like Kawaraban, which later became important contemporary newspapers like Yomiuri Shinbun, also flourished during this time. The state was a multifaceted player in the print revolution, encouraging the private sector but enforcing stringent censorship, especially against Christian proselytizing and political propaganda. In spite of this, foreign works kept coming into Japan and impacted Japanese print culture greatly.

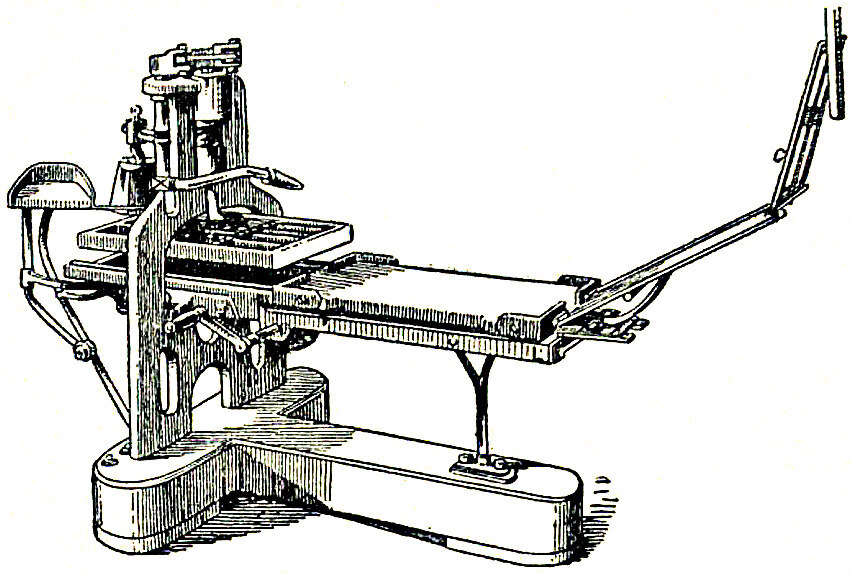

Later on in the future popular literature from former eras was still extensively read by the late 19th century. But the 1890s saw the industrialization of printing, bringing with it steam presses and new moveable type, which completely changed the printing industry. The mass production of inexpensive books and magazines in the 1920s opened up literature to readers from lower socioeconomic groups. The Kyōyōshugi movement fostered a culture of self-cultivation by connecting reading with personal growth. The 1960s saw the growth of the manga business and the modernization of the magazine trade, which by the 1990s had a worldwide influence. Japanese publishers remained important to academics, putting out standardized canons of key texts in philosophy and literature as well as extensive compilations of important works. The publishing industry has grown exponentially from the earlier time periods to now the amount of development seen is extensive.