Despite being a nation of immigrants, America has had a long and mostly negative relationship with them.

Going back as early as the 1790's, the immigrants who were coming to the country were largely Jeffersonian

(also known as Democratic-Republicans) and had political leanings that we would consider more liberal

today,

such as believing in rights for refugees, among other things. Those views angered the Federalist party—those against

immigrants—and encouraged the Federalists to take action. They pushed the Alien and Sedition acts

and it passed in 1798. As a result, many Jeffersonian (anti-Federalist) papers were censored and

the residency requirement for immigrants was raised from 5 to 14 years. The acts expired by 1801

with the change in presidency (Alien and Sedition Acts (1798)

), but those anti-immigrant sentiments

still remained in minds of many Americans.

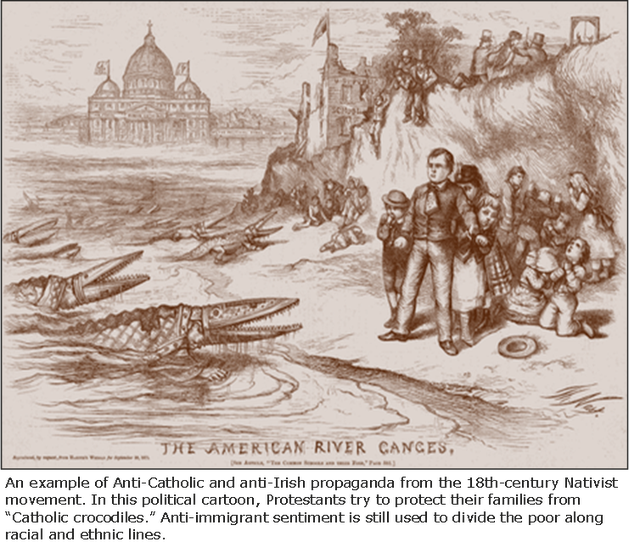

In the 1830's the majority of immigrants entering the country in particular were coming from

poor Catholic countries like Ireland, leading to an American political scene filled with anti-Catholic sentiment.

As Nancy Lusignan Schutlz describes, an increasingly urbanized and industrial society was transforming the American

agricultural economy, and working-class families flocked to cities to earn a living

(Schultz viii). The American

public was distrustful of the Irish Catholic immigrants coming into the country; so much so that in 1831

they burned down a convent in Boston. In a society where religion was

an indication of loyalty, everything that was not Protestant was not trusted; and consequently, anti-Catholic

propaganda was prominent. (See image)

With rapid social change during the antebellum period in the US, growing tension rose and prejudice

against marginal groups sparked Nativist movements, resulting by the 1850's in the formation of the Know Nothing

Party, known also as the ideological forefathers of the Ku Klux Klan

(Schultz viii).

According to The Know-Nothing Uproar

by Ray Allen Billington, one prominent Puritan from New England

who had a lot to say regarding Catholicism was Samuel F. B. Morse. In addition to inventing the telegraph,

Morse was a staunch Federalist and Calvinist who--in the same year that Awful Disclosures was published--ran

for mayor of New York as a Nativist Party candidate and on an anti-immigrant platform. Earlier, in 1830, Morse went

to Rome to watch a papal procession, and while there a soldier hit his hat off of his head. Whether it was actually

on purpose or on accident Morse declines to say, although it is clear he believed it to be purposeful and, from that

day on, he despised all Catholics. Upon returning home to America he published what happened to him in Rome, and

detailed exactly what he thinks about all the Catholic immigration to America. In his mind, he believes that

every single immigrant coming over is a devout Catholic intent on converting the country. The only solution

to this problem, he says, is to not let them in.

Eventually, around 1835, a name came about for the anti-Catholic party: No-Popery.

They were against all things Catholic and

strongly Nativist, meaning they were also against immigration and believed America should

remain closed to all but those who already lived there. And they were not the only party

formed which were against Catholicism: the Protestant Reformation Society and the New York

Protestant Association, among others, joined forces to try and expel all Catholics from the

country. They accumulated their funds to create powerful Nativist propaganda and encourage people to join

their cause (The Dublin Review, 162-3). One of the most popular forms of Nativist propaganda were

convent narratives, stories of nuns who are trapped

in Catholic convents and eventually escape.