In the early 19th century, a large number of anti-Catholic literary works found popular demand and circulated

widely throughout the United States. Between the years 1830 and 1860 approximately 270 books, 15 newspapers, 13

magazines, a multitude of giftbooks, almanacs, and pamphlets were dedicated to the anti-Catholic cause

(Pagliarini 97).

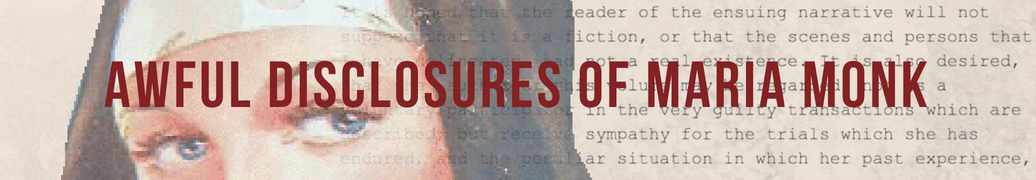

One of the most effective means of anti-Catholic propaganda came in the form of a literary subgenre typically referred

to as convent narratives. Stemming from the established gothic, Indian captivity...and a long European tradition of

anti-Catholic literature,

convent captivity literature captured wide appeal from paranoid native-born Protestants

(Schultz xix). Set in convents (rather than the castles more conventionally found in British gothic novels), these

order.

Like earlier Native American captivity narratives, they foregrounded the suffering of white middle- and upper-class

women in order to condemn their captors--who were othered in this case by their religious rather than racial identities.

And like the contemporary genre of city mysteries, convent stories exposed corruption and sexual deviance at the heart of

the city. At the time, anti-Catholic books were gaining popularity and generated interest because they posed as anti-Catholic

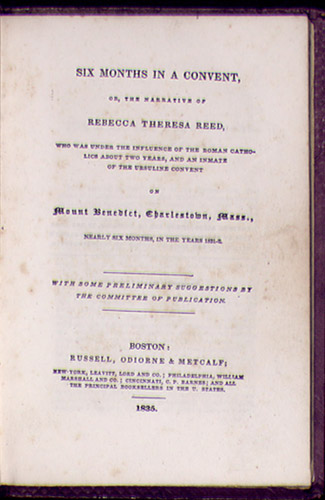

nun confessionals revealing the supposed debauchery and cruelty inside the convent. The first of these was Six Months

in a Convent (1835),  published in Boston, a novel about a former nun named

Rebecca Reed.

published in Boston, a novel about a former nun named

Rebecca Reed.

The wide popularity of the confessional tales of escaped nuns comes from the antebellum periods' emphasis on the cult of domesticity.

The representation in these books of Catholics as sexual deviants, and a threat to gender norms and family values, further strengthened

Protestant identity (Pagliarini 98). Early American convent narratives' fascination with middle-class women's

purity and with nuns' and

priests' sexual deviancy deployed ideas about gender and sexual norms for Protestants during the antebellum when these women experienced

the role of wife and mother raised to the status of cultural and religious icon,

and also revealed Protestantism's limitations

(Pagliarini 98).

Captivity narratives formed a way of establishing sexual norms and gender codes through the creation of sexual deviancy,

and

the limitations of Protestantism through the lack of restraint the True Man

has over their desires; and the ideology that the True

Woman's

was passionless, and place was to be concerned with piety, purity, submissiveness, and domesticity,

taking care of the

family and the home was now a destiny (Welter 151).

During the 19th century, in a society whose values changed frequently, where fortunes rose and fell with frightening rapidity,

where social and economic mobility provided instability and hope,

Americans had a newfound stability in the True Woman (Welter 151-2).

The Cult of Domesticity found way into the hands of many through the popularity of prescriptive literature during the time, in the

forms of sermons, advice manuals, magazines, and books

that told Americans how and why they should restrain their sexuality

(Pagliarini 99).

By invoking the whore of Babylon,(See Image)

; that, and the detail-oriented map of the nunnery all vouch for her authenticity, though her complicity in sacrilege

and immoral behaviors in the convent would make her part of societies' lowest of the lowes (Griffin 102). During this time of the century,

it was said that a woman was considered sensible when she knew her dependence on men. Though describing women as naturally religious seemed

desirable and empowering to some, it put the pressure on women to supplement and carry the burden of the man who goes to  the traditional Protestant metaphor for the Roman Catholic Church, Monk's epigraph figures

the convent as the body of the scarlet woman: 'Come out of her, my people, that ye be not partakers of her sin, and that ye receive

not of her plagues'

the traditional Protestant metaphor for the Roman Catholic Church, Monk's epigraph figures

the convent as the body of the scarlet woman: 'Come out of her, my people, that ye be not partakers of her sin, and that ye receive

not of her plagues' work long hours

in a materialistic society,

or else they would be damned immediately as an enemy of God, of civilization and of the Republic” for

challenging the sacred sphere of the home

( Welter 151-2). This explains why the prefatory and editorial defenses of the escaped

nun's modesty

had be to made so insistently (Griffin 101).

Mad Jane is also an interesting part of the narrative that is evoked as she plays the role of a sort of madwoman

trope that was

seen before in novels like Jane Eyre. This dark character, like in Jane Eyre and in many nineteenth century women's works,

functioned as a double for Maria Monk, representative of women's deeper subconscious through the character of the

reclusive virago

woman -- in this case the nuns and especially the Mother Superior who acted as accomplices to the alleged disgraces in the convents

-- are warned to fear and loathe, or else it would shatter patriarchal Protestant familial, sexual, and societal norms (Schultz xxvi).

As such, inspired by domestic narratives that had traced women's sense of empowerment to that literature, the escaped nun's narrative

is focused on seeing the plight of woman's purity as fallible, serving to prove young women's incapacity to be trusted

to make her

own religious choices, and remains vulnerable without a man. Escaped nun narratives, which were mainly written by pastors, echoes

mainstream writers emphasis on women's spirituality like domestic narratives.

However, while convent novels were said to have been read for enlightenment, these books served as erotic, sensationalist fiction

intending to draw Americans away from Catholicism, yet while the confessional narrative from someone who can be seen as a perpetrator

of such crimes destabilize[s] feminine spiritual, religious, moral authority that domestic novels instantiates

(Griffin 94).

Though both Reed and Monk portrayed physical abuse, what was most disturbing to Protestant readers was the way that the convents in

Boston and Montreal removed the control of female sexuality and reproduction from the Protestant patriarchy and permitted access only to

Catholics.

While Reed's themes focused more on how the education of women by Catholics would lead them to decide to become celibate,

Monk's work was explicitly depicting the sexual access that priest had to the nuns, with subterranean passages giving priests direct

sexual access to the nuns,

and the pit in the cellar where the babies of the nun's conceived by the priests would be thrown into after

they were murdered. The so-called reason Maria Monk had left the nunnery had been because she wanted to save the life of her unborn

child (Schultz xxi).

These graphic descriptions of violence and wrongdoings in the convents did not sit well with the general population. The publication

of Reed's narrative, for example, not only ignited a fire in its readers but literally ignited a fire at the Ursuline convent where her

mistreatment was said to have taken place (See Image). The Ursuline convent fire occurred in 1831 in the then-small town of Charlestown, Massachusetts;

today, it is known as the oldest neighborhood in Boston with prominent Irish-American roots. The convent burned while there had still been

nuns and children inside, all whom had escaped after a

These graphic descriptions of violence and wrongdoings in the convents did not sit well with the general population. The publication

of Reed's narrative, for example, not only ignited a fire in its readers but literally ignited a fire at the Ursuline convent where her

mistreatment was said to have taken place (See Image). The Ursuline convent fire occurred in 1831 in the then-small town of Charlestown, Massachusetts;

today, it is known as the oldest neighborhood in Boston with prominent Irish-American roots. The convent burned while there had still been

nuns and children inside, all whom had escaped after a misrepresentation

in a newspaper had audiences believe that an Elizabeth

Harrison was being kept hostage or worse murdered by the Catholics in the Ursuline convent. After there had been a few years before

about Rebecca Reed's horrible stay at the convent, readers were incited by their hatred for Catholics to burn down the convent not

long after the story had been released. Harrison was not trapped inside the convent, but had been accompanied back by her brother

after having experienced a breakdown and fled from the nunnery in a dramatic fashion (Schultz ix).