The Kojiki, The Nikon Shoki, and Premodern Writing and Language Culture

The Kojiki and the Nihon Shoki are the two oldest books of Japanese history. The Kojiki or "Record of Ancient Matter" was written in the early 8th century, between 711 and 712. It comprises a forward and three volumes (Tu 2). The book consists of Japanese myths, poems, and songs, writing about the universe's creation, the gods' birth, Japan's beginnings, and the Imperial succession. It was written by Ō no Yasumaro, a Japanese nobleman for Empress Gemmei (Pollack 15). It is often described as the 'Bible' of Japan and revolves around the ideas that Japan is a divine nation and the importance of the Emperor.

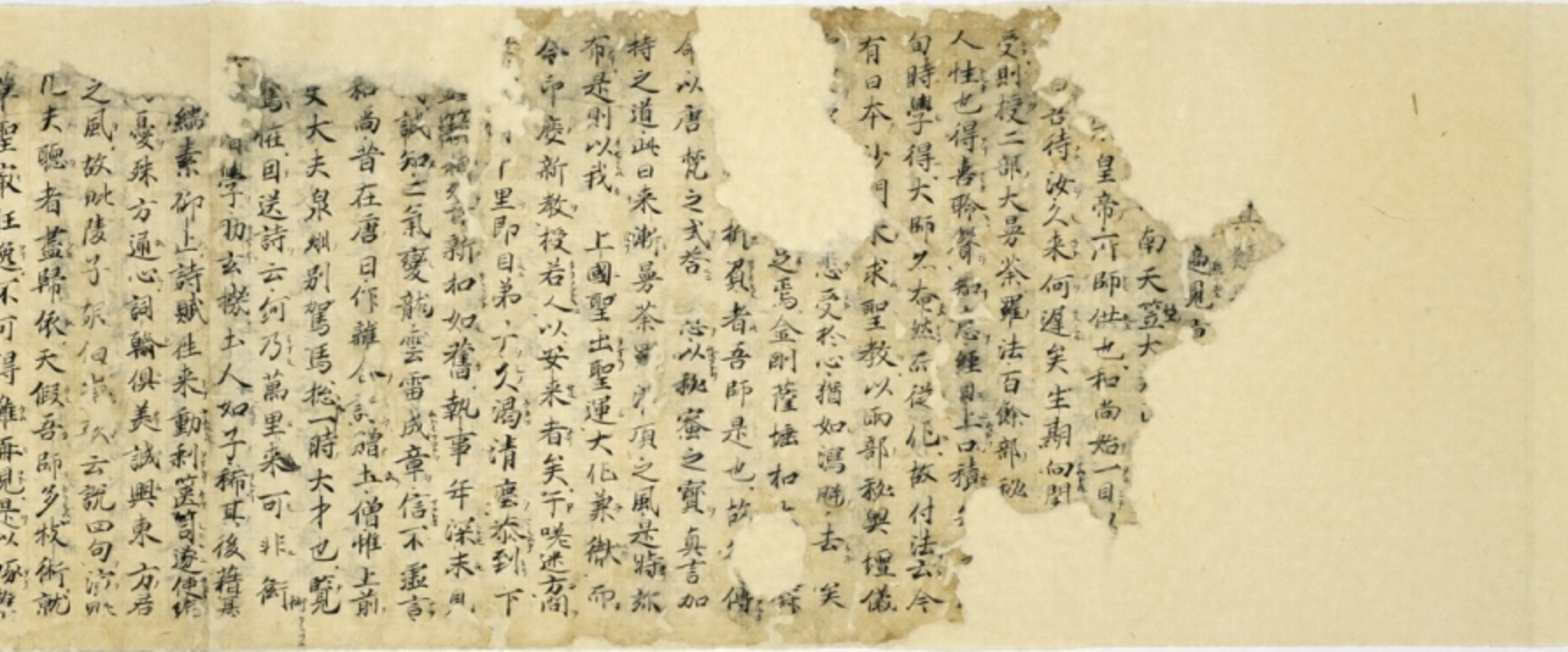

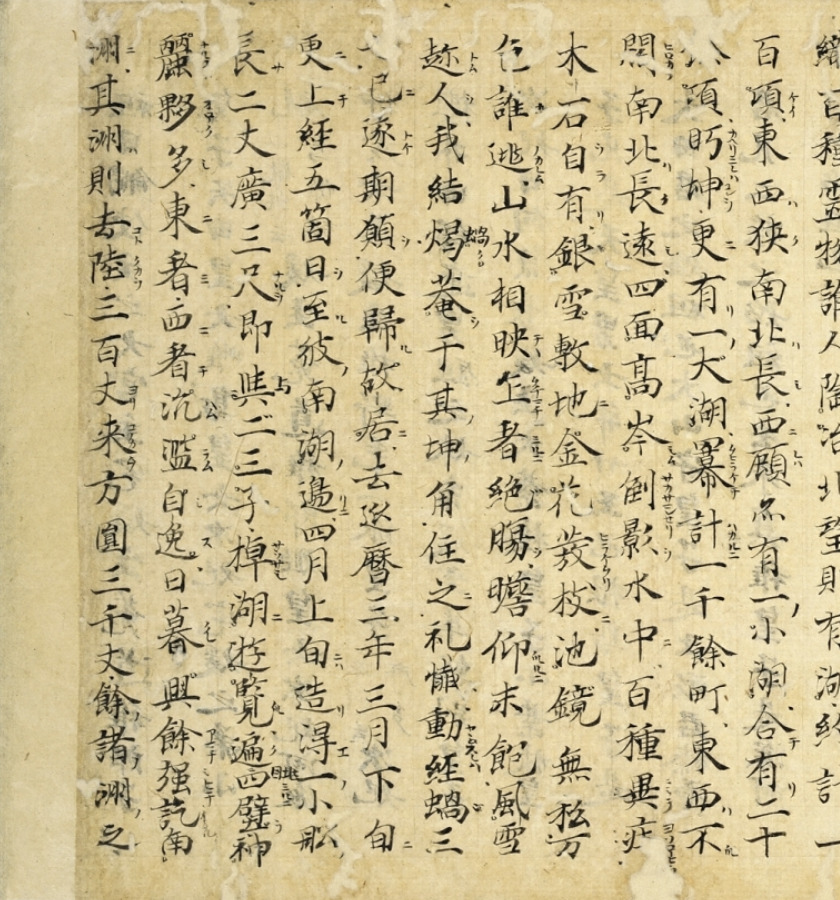

The Nihon Shoki, or "Chronicles of Japan," was written a few years later, in 720, and consisted of 30 chapters. The content in the Nihon Shoki and the Kojiki are very similar. However, the Nihon Shoki contained more detailed texts and descriptions than the Kojiki, and it is generally considered to be the complete historical record. In contrast, the Kojiki seems to be written more for entertainment purposes as it is written more dramatically and vividly (Tu 4). It was written by Prince Toneri and Ō no Yasumaro, and it was presented to Empress Genshō. They were handwritten on handmade paper using a brush and ink, as more modern printing forms had not yet existed.

Despite being Japanese literature, the Nihon Shoki and the Kojiki were written using Chinese characters. This is due to Japan having not developed its own written language yet. This use of Chinese characters to convey sounds from Japanese is called Man'yōgana (Schreiber 123). This provides a fascinating aspect to these writings, as the languages are entirely contradictory to each other within their phonological, morphological, and syntactic systems or their linguistic systems as a whole (Pollack 19). For example, in Chinese poetry, a significant aspect of their linguistics is end-rhyming, which uses ending lines with the same final sounds of characters to create rhymes, whereas Japanese poetry does not contain rhymes at all.

On the other hand, it relies on "pivot words," which are linking devices to connect meanings and create linear writings (Pollack 20). This process of converting Japanese into Chinese was made somewhat easier by the simplicity of the spokedn Japanese language at the time. At the time the Kojiki and Nihon Shoki were written, the Japanese language consisted of only eight vowels and thirteen consonants, which together made up eighty-eight phonetics.

The Nihon Shoki was written to chronicle Japan's history in chronological Chinese style, demonstrating that it was meant to be read in both China and Japan. In contrast, the Kojiki was written in a modified Chinese style that would appeal more to Japanese styles. Both texts served a similar purpose to the Bible, reflecting Japan's core principles. Their existence has impacted Japanese culture and lifestyles to this day.

The earliest example of Chinese writing being used to represent Japanese is on an inscription on a Buddha statue at the Horyuji Temple in Nara, from 607, around one hundred years prior to the Kojiki and the Nihon Shoki. It is believed that this writing was meant to represent Japanese and not Chinese because the syntax does not strictly follow Chinese word order (verb - object) and switches between Chinese word order and Japanese word order (object - verb), showing that the scribe's native language was likely Japanese rather than Chinese (Pollack 25).

Similarly, Korea also adopted the Chinese written language, referred to as Hanja. It was created around the second century and became popularized around the fourth century. It was used the same way the Japanese used it - by using Chinese characters to indicate either meanings or sounds in Korean, as they had not yet developed a written language for Korean. This was extremely complicated as it could be challenging to tell whether each Chinese character was meant to represent its meaning or whether it was meant to represent the sound, which restricted it to only elites. Later, Hangul was created in the 15th century, which is still classified as the premodern period. This was much simpler, containing only 24 letters and taking people between 1 and 10 days to master. This was due to high amounts of illiteracy due to the difficulty of Hanja, and it became the native alphabet of Korea (Pae 338, 339).