For Your Eyes Only: The Push for Private Executions

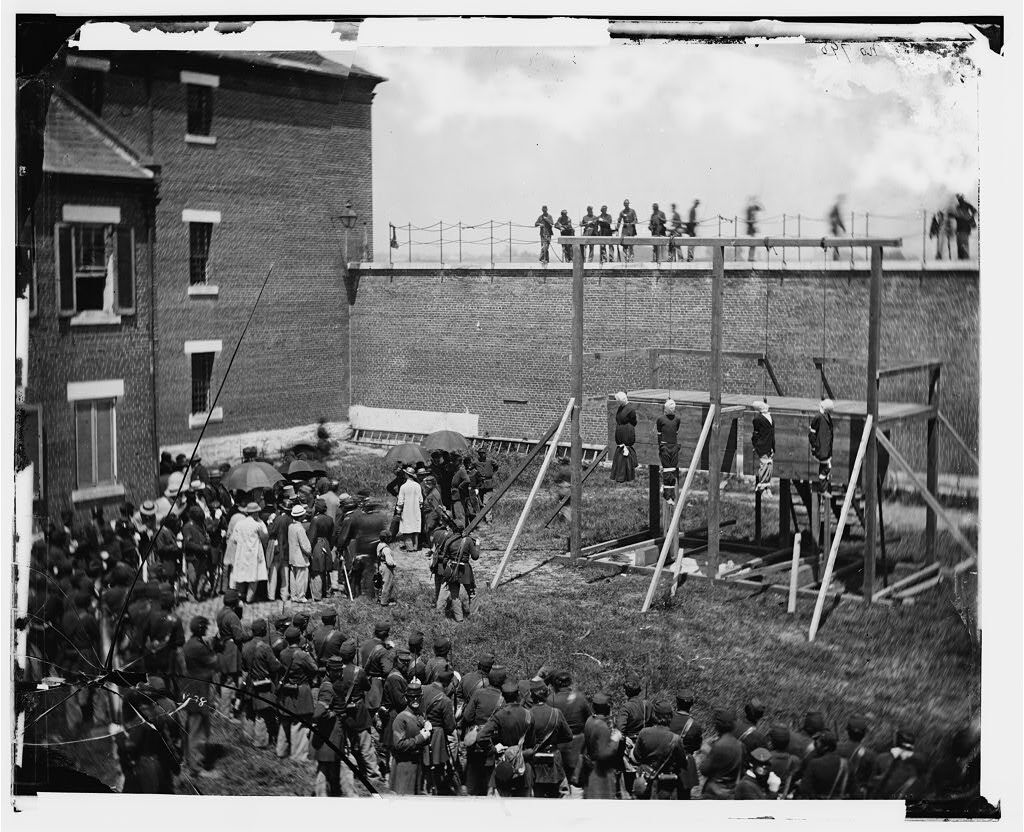

By the 1830s, growing concerns about public executions emerged in both the political and social sphere. Middle-class reformers worried that execution crowds were becoming unruly festivals that undermined rather than reinforced moral lessons. State authorities increasingly feared that large crowds posed risks of riot and disorder.

In 1835, New York became one of the first states to mandate private executions within prison walls. However, as legal scholar Michael Madow has shown, this transition was far from smooth or simple.

County sheriffs, responding to intense public interest, often undermined privatization by appointing hundreds of "special deputies" to witness hangings. This practice revealed the gap between state reform efforts and local popular demand for access to executions.

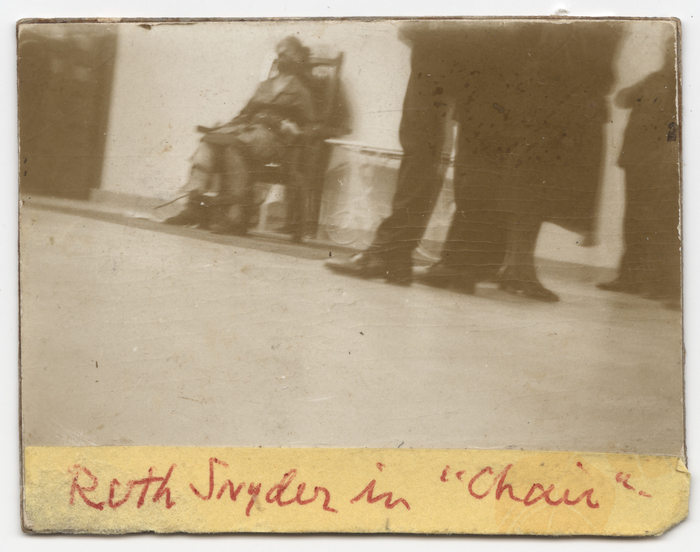

Perhaps no case better illustrates the public's continued fascination with executions - and the lengths the press would go to satisfy it—than the 1928 execution of Ruth Snyder in New York's Sing Sing Prison. Snyder, convicted of murdering her husband, was the first woman to die in New York's electric chair. Despite strict regulations against photographs, New York Daily News photographer Tom Howard smuggled in a small camera strapped to his ankle and captured the moment of her death. The photo, published the next day under the headline "DEAD!", became one of the most famous execution images in American history.

The sensation caused by the smuggled photograph led to stricter controls on execution witnesses, and the government increased its efforts to control execution imagery and media attempts to expose these supposedly private events to public view.

While generally supporting moves toward privatization, the press insisted on maintaining its access to executions and right to publish detailed accounts. When New York attempted to ban publication of execution details in 1888, newspapers successfully fought back, establishing their role as public witnesses.