Childhood Experience and Civil Rights Crisis

Childhood Experience

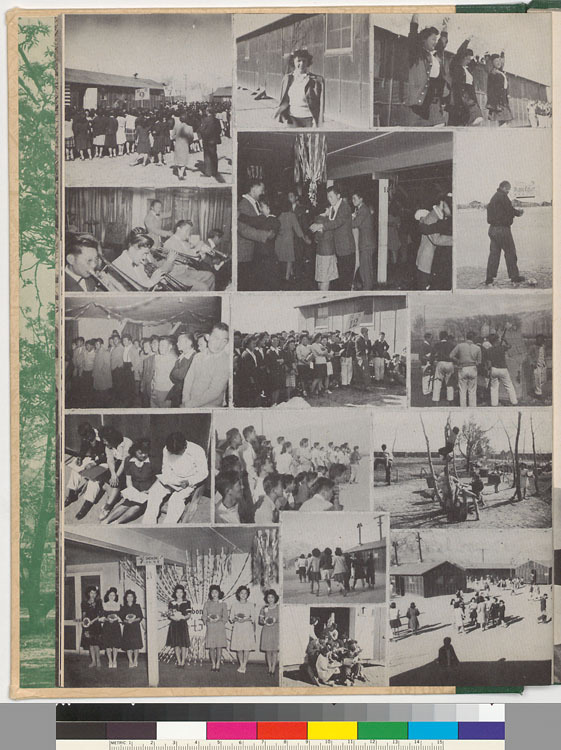

“The only living memories of World War II will soon be those of childhood” (Harth, 367). The life of a child living in Manzanar was far from the life a child is supposed to experience, especially for those who ended up at the children’s orphanage at the Manzanar camp. A young girl who was living there at the time with her parents who worked at the camp described Manzanar as “military-style dreariness” (Harth, 375). The young girl, now an author, Erica Harth described Manzanar to be scary, while also portraying certain beautiful aspects about a childhood in Manzanar. The clearest representation of life as a child in Manzanar was portrayed in the school newspaper. One child wrote, “on the positive side were ‘the mountains, the creeks, the trees and birds, the bright stars, the snow in winter, the good drinking water, the free food, the free electricity and water.’ Dislikes included ‘the desert, the sand storms, the hard winds, the cold winters, the fence around camp, a one-room home’” (Harth, 379). Another child wrote how they were “anxious” to leave Manzanar, and how they were tired of seeing the same thing everyday (Harth, 379). A fourth grader at Manzanar commented, “the Statue of Liberty eloquently sum up the mixture of pain, resentment, American boosterism, and innocent pleasure reflected in the interned children's contributions to the paper” (Harth, 379). Many of the children simply wished for a real home.

Although there were many discomforting memories of Manzanar, there were also some pleasant memories, too. Children were able to play different games, as well as play different sports like baseball, volleyball, golf and more. Importantly, “Japanese traditions were kept alive through judo and kendo and games like Goh and Shogi”(National Park Service). When it came to college students who were going to school in Manzanar, they were able to continue their education. “Camp teachers, counselors, and the Quaker-led National Japanese American Student Relocation Council assisted more than 4,000 students in leaving war relocation centers for schools away from the West Coast” (National Park Service). Even with the significant shortage of educational facilities and tools, many of the students were able to recover from their years at Manzanar and continue on to make a better life for themselves.

Civil Rights Crisis

The relocation and incarceration of Japanese Americans was a major obstruction of their rights and civil liberties. “The retraction of Japanese American citizens' rights and civil liberties is considered to be one of the gravest examples of what historian Mae Ngai terms a 'crisis of citizenship': a time when the constitutional rights guaranteed to citizens of the United States were upended and voided due to citizens' ethnicity and nationality” (Lynn Camp, 171). Because of belief in the idea that Japanese and Japanese Americans were a danger to national security, they were taken against their will with no power to fight for justice or their rights. Not only were their rights stripped, but pieces of their identity were taken, too. “The material environment of incarceration camps similarly denied Japanese Americans their individuality and ethnic heritage” (Lynn Camp, 171). Many former internees had strong words to say about the Manzanar internment camp. Former internees and next generations fought for the recognition of injustices and infringements of rights, and after a long fight, they won. In 1971, one of the Japanese internment camps “received official historic recognition” (Embrey, p.5). “The huge victory came in 1988, when the Civil Liberties Act of 1988 was passed, giving redress and reparations and an apology from the United States Government” (Embrey, p.10).