Elizabeth Van Lew

Before The Civil War

Elizabeth Van Lew was born in Richmond, Virginia on October 12, 1818. Her family was part of Richmond's "high-society" and owned slaves. Elizabeth was educated at a Quaker school in Philadelphia, which likely influenced her to support anti-slavery politics. After receiving her education, she returned to Richmond to live with her mother and was active in Richmond’s societal scene.

Both Elizabeth and her mother held some anti-slavery ideas and gave their slaves some means of independence and financial autonomy.

During The Civil War

Elizabeth's house was located only a few blocks from Libby Prison, a prisoner of war jail. Elizabeth and her mother convinced a General to allow them to bring food and supplies to the Union soldiers held there. With this access, Elizabeth was able to pass messages in and out of the prison, give the prisoners extra food and water, and even help them escape.

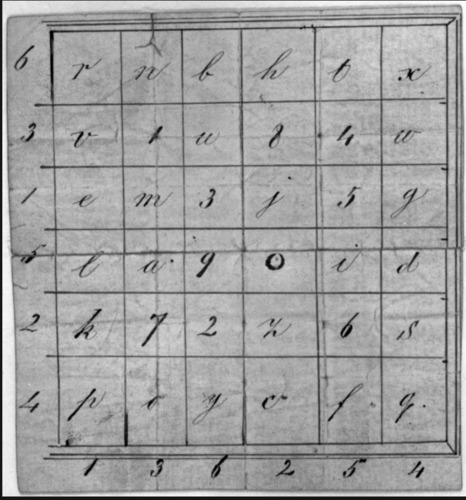

As the war carried on, Elizabeth's spread of information intensified. From the Union prisoners, she gathered information about the Confederate army's plans which she then passed onto Gen. Grant. After being recruited as a spy for the Union army, Elizabeth began to build a network of spies which eventually included 12 people, including former slaves.

Elizabeth worked hard to hide her support of the Union, staging public outings where she and her mother were seen helping the Confederate army and hosted a Confederate prison warden in their house.

Gen. Grant and his intelligence officer both acknowledge the quality and quantity of information Elizabeth provided to them. She also was granted a small stipend for her work.

After The Civil War

By the time the war ended, she had been ostracized from Richmond society and was labeled as a spy, a term that she did not approve of

“I do not know how they can call me a spy serving my own country within its recognized borders… [for] my loyalty am I now to be branded as a spy—by my own country, for which I was willing to lay down my life? Is that honorable or honest? God knows.”

Elizabeth's stipend did not cover the money she had put into the war effort, leaving her quite poor. This in addition to her support of other "radical beliefs" such as women's suffrage and civil rights, only exacerbated her isolation from her community.

In 1869, President Grant appointed Elizabeth postmaster of Richmond, a position she held for 8 years. However, when Rutherford B. Hayes became president, Elizabeth lost her job and was largely penniless.

In her 70s and without any money, Elizabeth turned to those she had helped in the war. The families of the Union soldiers she had helped and other wealthy people sent her money throughout the rest of her life.

Elizabeth died in 1900 and was inducted into the Military Intelligence Hall of Fame.

Sources:

“Elizabeth Van Lew (U.S. National Park Service).” National Parks Service. U.S. Department of the Interior. Accessed March 16, 2022. https://www.nps.gov/people/elizabeth-van-lew.htm.

“Elizabeth Van Lew.” American Battlefield Trust. Accessed March 16, 2022. https://www.battlefields.org/learn/biographies/elizabeth-van-lew.

Magazine, Smithsonian. “Elizabeth Van Lew: An Unlikely Union Spy.” Smithsonian.com. Smithsonian Institution, May 4, 2011. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/elizabeth-van-lew-an-unlikely-union-spy-158755584/.