Secularization

The Secularization of the Missions (1833)

When Mexico gained independence from Spain in 1821, they had control over the entire Californian front. Since many of the Mission Churchers remained loyal to the Catholic Church in Spain, the Mexican government wanted to dismantle some of the power that Mission Churches held.

Prior to the secularization act, the first Mexican-born governor of Alta California decreed a “Proclamation of Emancipation” on July 25, 1826 for any of the indigenous individuals who no longer wanted to be enslaved by the Mission System.

Later, on August 17, 1833, Mexican Congress passed the “Decree for the Secularization of the Missions of the Californias.” Not only would much of the Mission land be taken away and given to Mexican ranchers, but many of the provisions of the decree that were meant to ensure that the indigenous people would also receive some of the land and be guaranteed Mexican citizenship failed (Servin 133). In short, they did not receive the land that the decree outlined they should receive.

What ended up happening instead was many of the pasture lands were given away and most of the Mission Santa Clara buildings remained as parish buildings since, aside from the Dominican friars, there was not enough clergy to minister to the people. Later on, the ownership of the Mission Santa Clara de Asís would be handed over to the Jesuits from the Dominicans, which will be described in greater detail in the next segment of this exhibit.

What Happened to the Indigeounous People After Secularization?

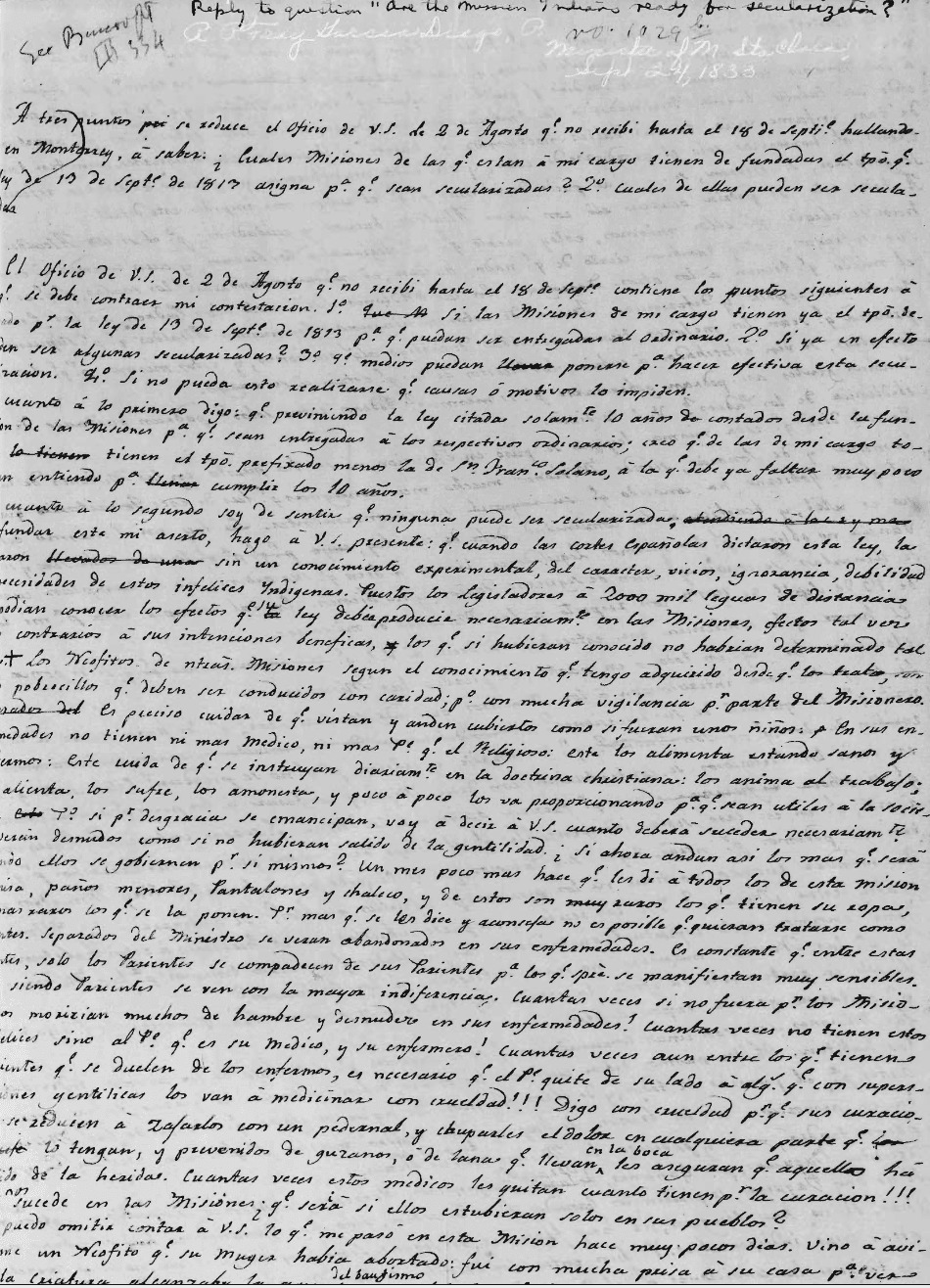

The document below is a letter written by Fr. García Diego's as a response to the Secularization degree. While no translation is currently available, the SCU Digital Collections says that he expressed concern that the Natives would not be able to sustain themselves without the financial and spiritual support offered by the Mission Churches.

Since secularization weakened the means by which the Santa Clara Mission made much of the money to finance their efforts, they would no longer be able to support the Tamien people when they left. Aside from that, he also claims that the Friars are the only ones who could ensure that the Indigenous People do not participate in superstition, drinking and abortion.

However, the argument made by Fr. García Diego may be a false narrative. According to ethnohistorian George Harwood Phillips, many of the Indigenous People willingly chose to leave the missions and also had no interest in continuing to be a part of the system that the Mexican government outlined for them, which included ownership of land (Philips 295).

According to Phillips, most of them “either sought work on the great Mexican ranchos then being carved out of the mission territory or wandered into towns to work intermittently and to drink and gamble.” (Philips 298). Regardless, it is clear that the situation of the Ohlone people became markedly worse after secularization as indicated by the rapidly declining population of indigenous people in the years following secularization due to fugitivism, low birth rates and disease.

To this day, the Ohlone continue the struggle of regaining ownership of the land that was promised to them by the Secularization Decree