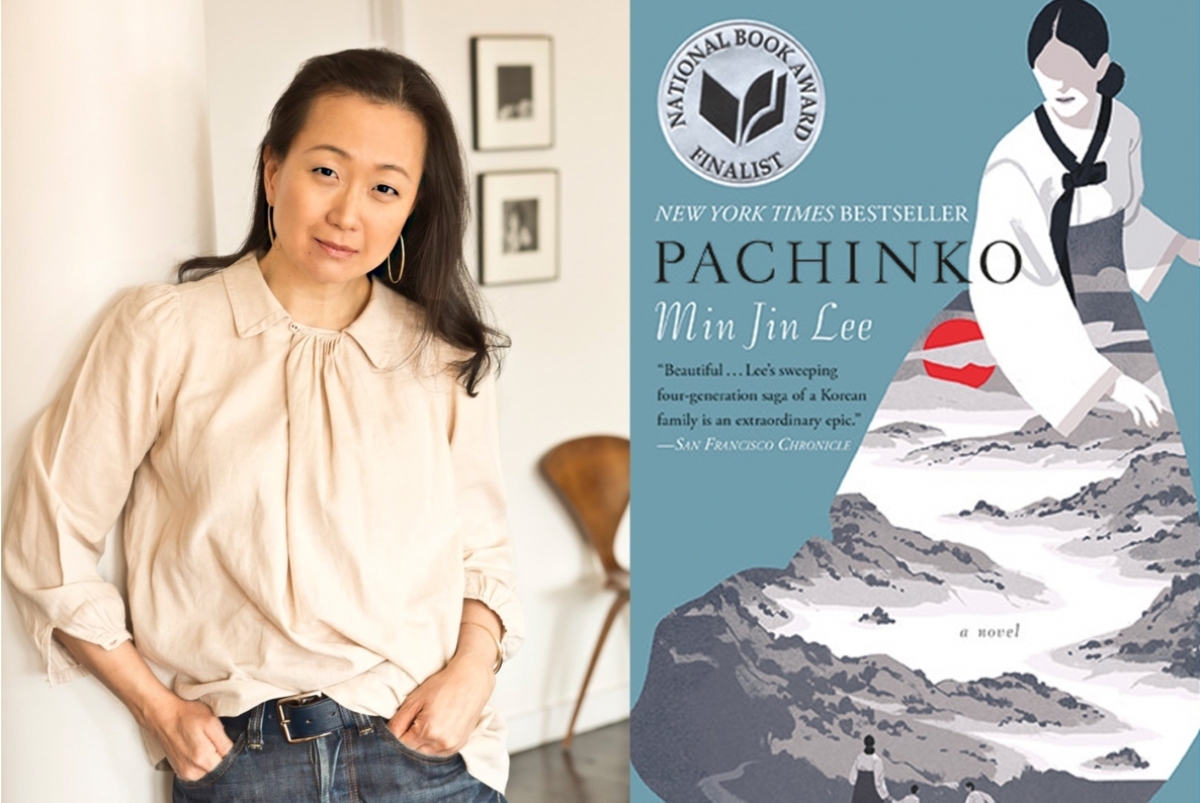

Searching in Min Jin Lee’s Pachinko

Continuing with self-journey in modern literature, Min Jin Lee's Pachinko weaves this journey and interplay through exploring the many lives of Zainichi Koreans over several generations in Japan. In the novel, there is an enduring struggle between maintaining cultural heritage while confronting prevalent discrimination and societal exclusion in a country that views them as outsiders and inferior. Looking at the generational perspective of the Zainichi Koreans, "First-generation Zainichi considered themselves temporary guests in Japan and had every intention of returning to Korea. Second- and third-generation Zainichi, however, were more interested in permanent status in Japan" (Roh 59). This section will focus mainly on the second- and third-generation Zainchi.

The most prominent self-identification journey in the novel is the contrast between the brothers, Noa and Mozasu. Noa strived to assimilate into Japanese norms, hoping to be considered "normal," which was to be Japanese during that time and place. Throughout the text, he continued to reject his Korean identity, growing up to try and be the perfect Japanese student. He got into one of Tokyo's prestigious universities, Waseda, and continued to be scholarly and assimilate into being "Japanese" (Lee). However, we see a slight shift towards the end of Book II: Motherland, where Noa has a sudden realization about whom he wants to be with his Japanese Girlfriend, Akiko: ". . . in fact, [Noa] did not care about being Korean or Japanese with anyone. He wanted to be, to be just himself, whatever that meant; he wanted to forget himself sometimes. But that wasn't possible. It would never be possible with her" (Lee 308). He comes to self-realization of his identity that, regardless of how or what society conforms him to be, at that moment, he wants to be himself; he wants to be Noa. He believed "that if he becomes an ideal student and son, he 'would help the Korean people by his excellence of character and workmanship, and that no one would be able to look down on him'" (Tablizo 114). However, being of Korean decent and having a family member as part of the Yakuza, Noa felt as his own blood was tainted and is "irredeemable" (Tablizo 115). Being Japanese and constantly running from his Korean heritage seemed like the only path to being "normal." However, the first generation wildly looked down upon this since it meant leaving your Korean Heritage behind and in the dust. "For many individuals, naturalization has often brought criticism from co-ethnics and isolation from the Korean community" (Hester 139). It brings conflict into one's self-identity as one side sees it as betrayal, and the other does not accept Koreans into their society as one of their own, despite learning and living in Japan. In the next part of the novel, Noa does become a Japanese citizen and is perceived as a Japanese man by the people around him. However, the weight of being Korean is carried forward "like a dark, heavy rock within him. Not a day passed when he didn't fear being discovered" (Lee 358). Eventually, Hansu and Sunja find him, almost as if the weight caught up to him, killing him because he cannot handle it anymore (Lee).

On the other hand, Mozasu did not attempt to assimilate into being Japanese, but instead conformed to the stereotypes society has put upon him: Dirty Korean or "Korean Fool (Lee 241). In the novel, it is described that Koreans got into "trouble" with the Japanese Police. When one got arrested, the whole culture was to blame for it. Because they were already considered inferior by Japanese society, these incidents turned into stereotypes. Mozasu believed that "he was becoming one of the bad Koreans" (Lee 243). He knew that ". . . society will never change the way he is treated . . ." (Tablizo 116). Unlike Noa, who worked hard to be an upstanding Korean citizen to be accepted by the Japanese, Mozasu was accepted by the Japanese by being Korean and conforming to the stereotypes. In this context, both were striving for "acceptance" into society, whether trying to assimilate or conform to the notions already put into place. The interweaving of identity and culture is universal, as we see with Noa and Mozasu's experiences, but they are often unique and perceived differently. When Mozasu visits Korea, the supposed "homeland," he realizes he is also not welcomed there either. "Where we gonna go? . . . In Seoul, people like me get called Japanese bastards, and in Japan, I'm just another dirty Korean. . ." (Lee 377). Mozasu has an identity crisis "is reinforced after facing the ambiguity of being neither Korean nor Japanese" (Tablizo 112). Both cultures that Mozasu has known his whole life rejected the idea of him being. So what makes him him? What is his culture? His self-identity? However, whether he is one or the other, neither or both, reinforces the complexity of cultural identity. It will always be incomplete, thus the soul searching for more and a place.

This distinction within Pachinko shows the complexity and uniqueness of an individual's cultural identity journey. The contrast between the brothers, Noa wanting to become Japanese and Mozasu conforming to the Korean Stereotypes of the Japanese places, shows their hybrid identities of Korean and Japanese influence. In both cases, their Korean identity was their foundation built upon by their interactions with Japanese culture. Noa could not run away from it, and Mozasu built upon it. Their stories reflect the evolving and ongoing struggle to define oneself in a society that views them as perpetual outsiders.