Sounds

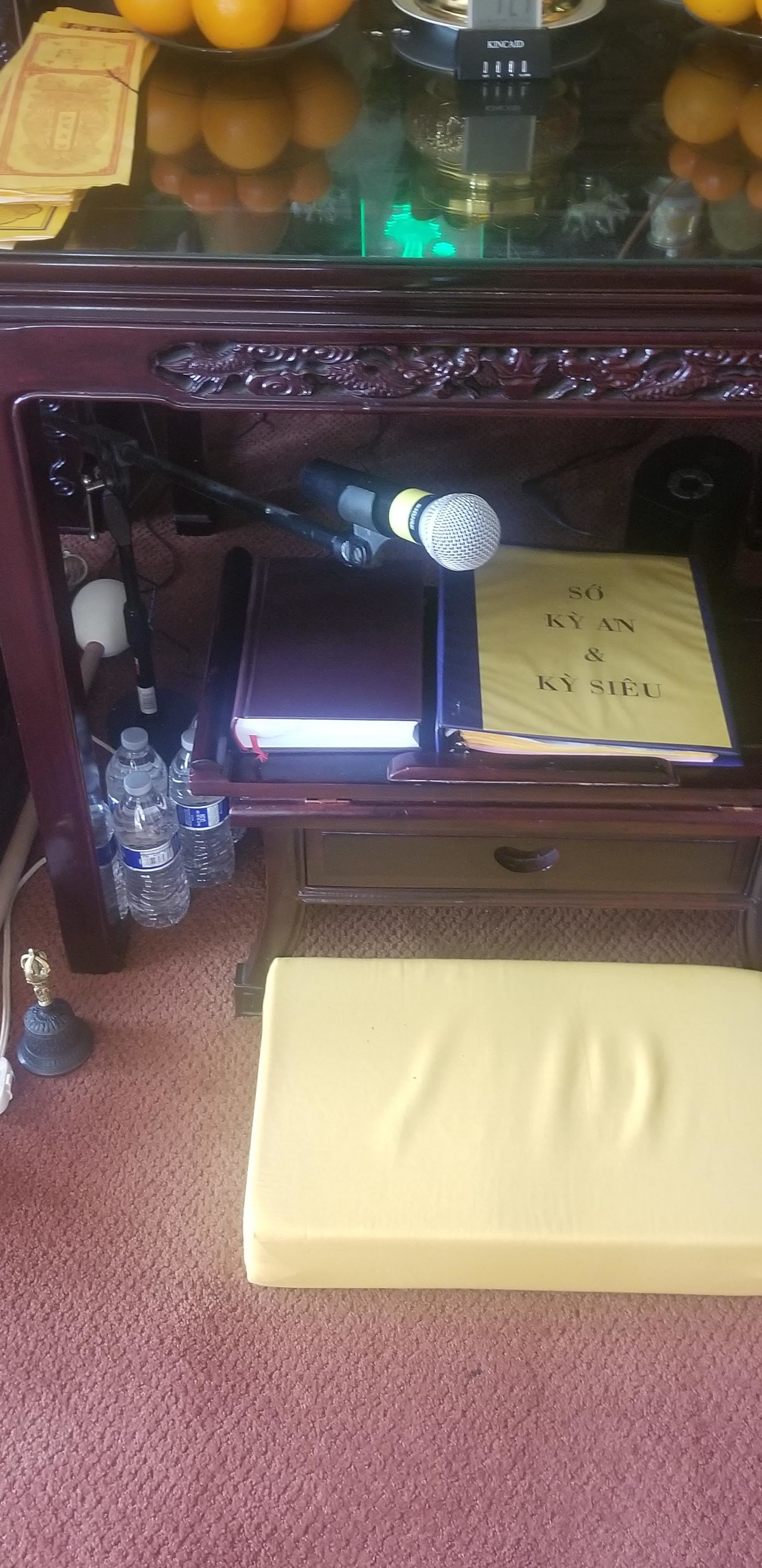

The lead monk at the temple typically conducts Buddhist rituals to honor the deceased and a crucial aspect of these rituals are the chants that he does. Included to the left is an image of a microphone that the monk typically uses to project his voice and a recording of a typical Buddhist hum that is recorded and replayed to be heard throughout the space. These sounds are important to the temple because sound "is a powerful affective register: soundwaves travel through the air and vibrate not only our eardrums, but our entire bodies. Whereas sight works in straight lines—we have to look at something to see it well—‘hearing is hemi-spherical; we hear sounds from all around us, not just where we cast our ears’” (DeLaure 11). These sounds help ground the user's experience of Buddhism because it communicate to the audience the spiritual meaning of the many different rituals to honor the deceased.

This communication is most evident when examining how certain Buddhist chants creates signals to the audience to perform certain tasks. One of the most crucial practices at Tu Lam temple is when the lead monk will conduct services to honor the deceased. Often, family members will kneel down and bow their heads three times when a certain signal is heard from the monk's chants. This signalling allows the audience to become part of the ritual to honor their loved ones. This act would what DeLaure describes as spatial memories which “engage bodies via multiple senses, such that audiences are not merely spectators, but active participants in the memorial-as-performance” (DeLaure 9). Because the audience becomes active participants in the rituals at the temple, it allows them to have a more tangible experience of honoring their loved ones.