Reflection of the Italian-American experience

Context: Relation to the Italian American Experience

Sobrato's journey from humble beginnings to gigantic success and billionaire status shows the grit of first-generation Italian-Americans and their children and the rapid social transformation and assimilation of Italian Americans in the 19th and 20th centuries. These Italians started as humble immigrants, often the subject of poverty, crime, prejudice, and discrimination, and grew to the status of respected thought leaders, politicians, and business people whose whiteness and Americanness today are not questioned. Granted, Italians historically shared a much better reputation on the West Coast than the East Coast. Still, they faced discrimination and challenges in many ways, such as having to prove their Americanness during WW2, labor exploitation, and housing discrimination and segregation.

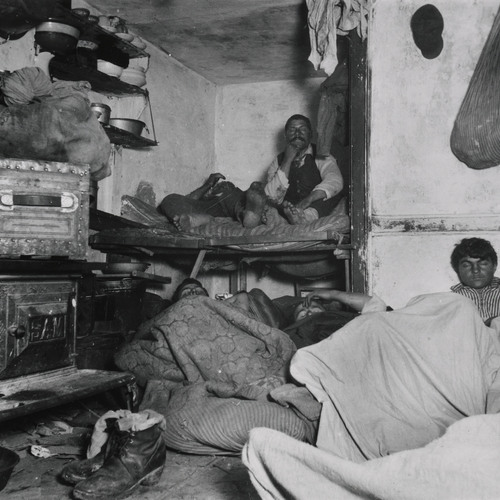

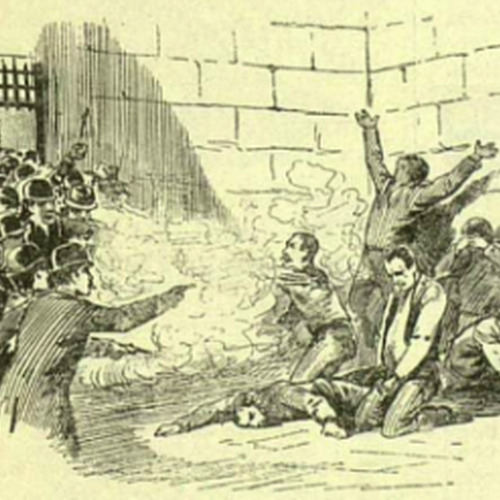

Before diving into the challenges Italian-Americans faced in California, it is crucial to understand the greater context. As noted above, discrimination against Italians in California was much lighter than discrimination against Italians on the East Coast, Midwest, and South. Historian Donna R. Gabbacia remarks, "The story of Italian Americans in the West is a largely upbeat one. The stories of upward mobility, a fairly rapid economic success, attainment of education relatively quickly compared to the East Coast" (Norelli). On the East Coast, in New York, Italians lived in filthy tenements, worked unsanitary industrial jobs, faced crime without police protection due to isolation from authority, were associated with the Mafia, and faced countless more issues (Laurino). In the Midwest, particularly in Chicago, Italians faced similar issues, such as housing discrimination from Swedes who wanted to segregate the groups (Laurino). In the South, discrimination against Italian Americans was so terrible that a mass lynching of Italian Americans was carried out by a mob in New Orleans in 1891 (Laurino).

These injustices on the East Coast, in the Midwest, and in the South were based on prejudices against southern Italians. However, the main Italian regions that exported Italian immigrants to California were more north; California received more Italians from northern regions like Genoa than states in other regions of the U.S., whose Italian immigrants largely arrived from southern Italian regions like Sicily and Calabria (Norelli). The larger presence of northern Italians was a better look for Italians in California because of northern Italians' better reputation. As more southern Italian Americans arrived in California, the existing Italian population aided them so that they would assimilate and rise to higher classes of American society, protecting the image of Californian Italian-Americans. Sebastian Fichera, Author of Italy on the Pacific, describes, "Between 1890 and 1914 the community grew a lot larger. There was a leadership ready to go among Italians and they were ready to start organizations that integrated the incoming population of Italians. The prominente didn't want to have a high concentration of Italian immigrants who were unskilled in one place because they were afraid of what it might look like..." (Fichera 248) The American mainstream generally thought Northern Italians to be smarter and more civilized than Southern Italians. Northern Italians were associated with the Renaissance, while southern Italians were associated with poverty and crime. Thus, the northern Italians had to help the southern Italians assimilate and prosper in California so Italian-Americans could maintain their status as a group.

Italian-Americans in California were also higher on the racial hierarchy in California, which included African-Americans, Latinos, and Asian-Americans. Author and Stanford lecturer Carol Lynn McKibben remarks, "There was a tremendous racial diversity in California starting in the mid-19th century with the Gold Rush. There was a line drawn between people who were of European origin and people who were Asian, people who were Mexican" (Norelli). The presence of these other more distinct groups of people made Italians better blend into a white identity. They enjoyed many privileges of being white; this was especially important when World War 1 arrived. Gabbacia explains, "California passed laws prohibiting, ah, Japanese and ultimately other Asian groups from purchasing land. Italians were not subject to that nor were any other southern and eastern European immigrants" (Norelli). Because Italians were still considered white due to their distinction from other races in California, they enjoyed many privileges.

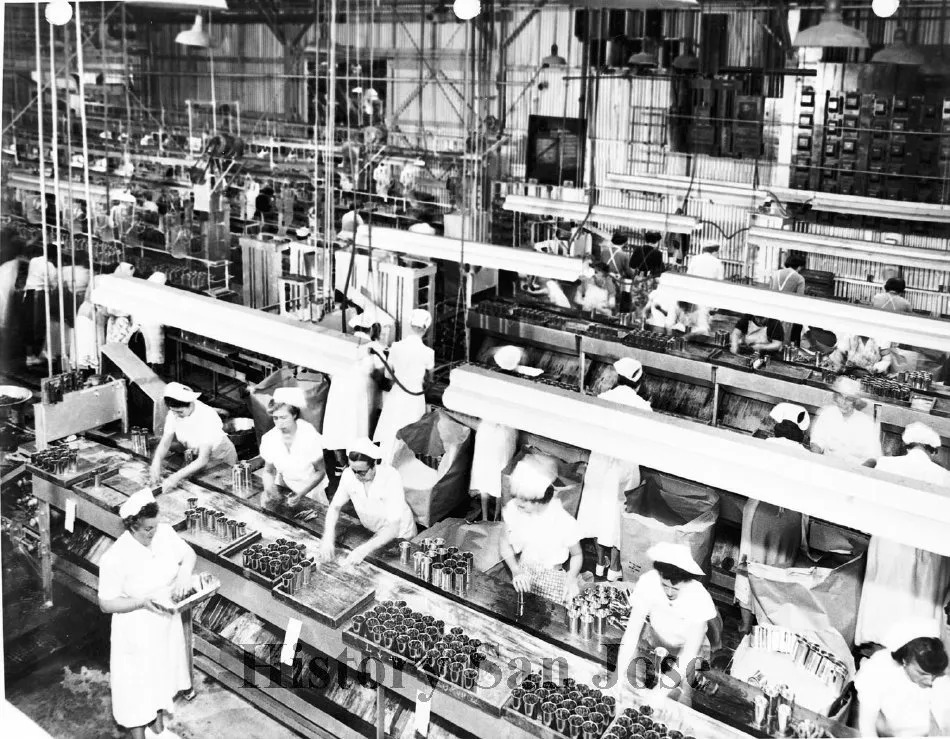

Even though Italian Americans enjoyed more privileges on the West Coast than in other parts of the U.S., Italian Americans were less established than Anglo-Saxons, which led to many economic challenges and discrimination. For instance, many Italians in America experienced poverty and poor factory working conditions. In the 1920s, Marco Fontana, the founder of Del Monte Canneries, created his business model of manufacturing cans of fruit in California to sell to the large New York market. Professor Emerita at Saint Mary's College California Paola Sensi-Isolani explains, "Fontana … came here and started his work with the canneries. Who did he hire? He hired the Italians who did not have the education and how much did he pay them? He pay them much less than he would have had to pay non-Italians. Most of the workers in these canneries were women and the working conditions were really abysmal" (Norelli). Although Italians were mainly wine and grape farmers and fishermen in California, like on the East Coast, many poor urban Italians had to resort to poor working conditions in low-skill jobs and living in poor conditions.

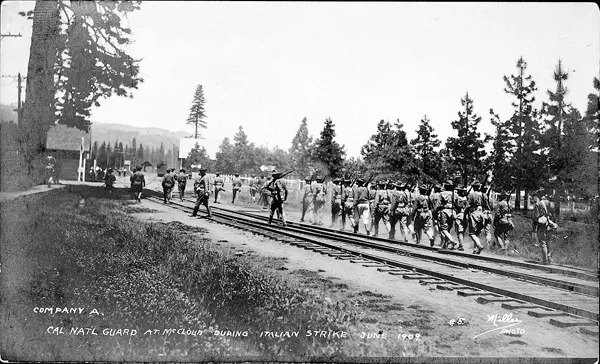

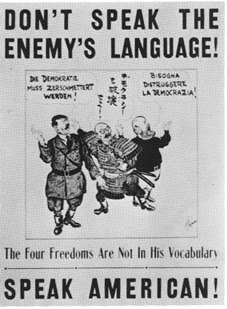

As described above, Italian-Americans were very wary of their public perception as a group; this was especially true during WW1, when "they were worried that just as the popular climate had turned against the Japanese and the Chinese popular climate, they were the next in line to go" (Norelli). Italy's initial alignment with Germany at the outbreak of WW1 made many non-Italian Americans suspicious of Italian Americans. World War 1 was just one instance of the crucial element of the Italian-American experience: feeling like you are on the edge of outsider status. In another instance of “conditional whiteness,” Paola Sensi-Isolani describes how the majority of Italian workers of San Francisco-based McCloud lumber camps "[shopped] in company towns with a high component of anti-Italian sentiment. [The McCloud Lumber Company] bunked many of them in the woods in segregated housing from the European lumbermen who complained because they were housed with Dagoes, and so they had to be housed separately" (Norelli). When Italian-Americans at the McCloud Lumber Company went on strike for not receiving the 25 cents per day way they were promised, the McCloud Lumber Company called the National Guard and accused Italians of violence. The press reported the strike as Italians putting white women and white society in danger, implying that Italians weren't white (Norelli). Sensi-Isolani elaborates on Italians' conditional whiteness, "When you get somebody like Giannini who is criticized by being called, ah, Dago huckster but at the same time Giannini is also described as being fair and more Northern European than Latin corroborating this dominant idea that you have to be a Northern European and look like one and behave like one in order to achieve" (Norelli). As Sensi-Isolani illuminates, the distinction of Italian-Americans from lighter Europeans still was present to a degree in California, as not all Italian-Americans could escape the sentiments pervading across the U.S. regarding Italian-Americans' inferior status, even the successful founder of Bank of America A.P. Giannini.

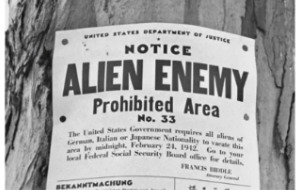

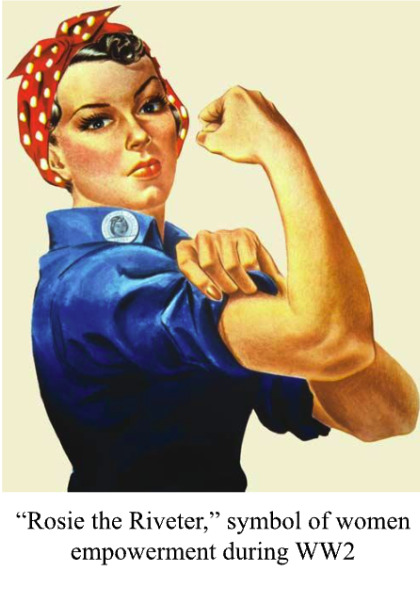

World War 2 distinguished Californians even more than World War 1 and led to some serious injustices, especially on the American West Coast. After the Japanese bombing of Pearl Harbor, President Roosevelt declared any undocumented person from an enemy nation an "enemy alien," instantly turning 600,000 Italians into enemy aliens (Norelli). General DeWitt especially kept an eye on the Italians on the West Coast for enemies of the state (Norelli). During WW2, authorities banned Italian-American fishermen from Fisherman's Wharf, and 10,000 Italians had to relocate (Norelli). In many cases, the government sent Italian Americans to internment camps based on little to no evidence. For instance, Lawrence DiStasi tells how authorities profiled, arrested, and humiliated his Father and uncle due to their "alien enemy" status, "After they were arrested, someone took a picture of my dad and my uncle being handcuffed and it showed up in the San Jose Mercury News on the front page with the headlines of enemy aliens are rounded up locally. And so my dad is in this picture ... you can see that his face looks red and embarrassed and ashamed that this would happen" (Baliza). American authorities subsequently interned DiStasi's father at a camp in Missoula, Montana. DiStasi's father writes in a letter, "I was accused of being potentially dangerous, alien treated and regarded as such after my arrest, after all this time in the enclosure. I do not yet know why. All this must be some reason for some evil. I do not know. Something wrong? Somewhere. Except I am not a citizen of this country" (qtd. in Baliza). The actions taken against Italian Americans during World War 2 completely "othered" them and justified their unjust discrimination and oppression. The U.S. government has yet to apologize for many of the injustices committed against innocent, loyal Italian Americans.

This Italian-American history sets the stage for the story of John A. Sobrato, who was born in 1939 near the start of World War II. Sobrato's lifetime would, by and large, see the rapid economic improvement of Italian-Americans, which Sobrato certainly took part in, and their further assimilation into American society.

A rigid understanding of Italian American history is vital for understanding John A. Sobrato's success in the context of the "Italifornian" and Italian American experience. Many aspects of the historical Italian-American experience are reflected in Sobrato's life, and many parts of Sobrato's life exemplify how much the Italian American experience has changed. Unlike many past Italian Americans, like A.P. Giannini, people do not question John A. Sobrato's "whiteness" or "Americanness." Likewise, Sobrato does not have to prove his loyalty to America like the Italian-Americans during World War 2, whom the U.S. government treated as "enemy aliens." People are not shocked by the Italian American's billionaire status, as many Italian-Americans are now quite wealthy; Californian Italians have indeed come a long way from making modest livings as fishermen, farmers, and industrial workers on their first arrival on the West Coast. Despite descending from a heritage of a people once discriminated against, the target of perceived inferiority from racial pseudoscience, and the subject of segregation, John A. Sobrato's grandson, John Mathew, points to how much privilege he was born with. After working with the largely Hispanic East Bay schools, John Mathew remarked, "There were just so many things that I had never considered before, because my own privilege, my identity and my network largely insulated me from ever having to confront those challenges" (Adenji). John Mathew is a living example of how Italian-Americans have improved so well socio-economically that now they are a group whose people often consider themselves privileged in many respects.

Far from being considered "enemy aliens" like Italian-Americans in World War II and victims of persecution and oppression by the U.S. government, John A. Sobrato's family spends considerable time working with the government, drafting legislation proposals and lobbying the government to advance its philanthropic "democracy" initiatives of reforming the American electoral system (Adenji). The fact that Italian-Americans were once targets of government oppression and now are major political influences in America (not to mention Italian-American politicians like Nancy Pelosi) demonstrates their rapid increase in status and assimilation into American society.

Many aspects of John A. Sobrato's life are products of Italian American history. For example, like the hundreds of thousands of Italian Americans who made up 10% of U.S. soldiers during World War 2, Sobrato's Father supported America's WW2 war effort by working as a chef. Like many Italian-Americans, Sobrato's Father proved his loyalty to America by supporting the American military.

Sobrato's education and beliefs are also partly due to changes in Jesuit education in America, especially at SCU, throughout their history in the American West. McKevitt describes how Jesuit schools in the American West were "Caught in perpetual ambivalence; the Italian school masters struggled to strike a balance between two dynamics central to their schools' existence. Like other transplanted educators, they sought to bottle the wine of a centuries-old European educational tradition and dispense its riches in America. If they assimilated American culture to excess, they argued, that heritage would be diluted and lost. On the other hand, too much emphasis on the past would isolate the schools from American society and culture. Accordingly, because Catholic establishments existed to prepare you, people, for roles in that society, they had to accommodate themselves to the norms and requirements of the United States" (McKevitt 210). In the early years of Jesuit education in the American West, Jesuits often had to trade their Jesuit values of a well-rounded education to meet the needs of Americans who were materialistic and focused on commerce. McKevitt writes, "Despite its popularity, Jesuits privately dithered about the worth of vocational education. Many Italians steadfastly opposed the commercial course, because it undermined Latin and Greek and because it seemed a surrender to materialism. Accustomed to a world shaped by tradition, the Jesuits now found themselves in one driven by Mammon, as a visitor to California once observed, 'The Americans think only of dollars, talk only of dollars, seek nothing but dollars; they are the men of dollars.' Schooling in mercantile subjects might be 'greatly suited to the temperament and training of Americans, who from their very cradle are engaged in the accumulation of money,' another priest charged, 'but it is very foreign to our customs, by which boys are educated in the study of the humanities and natural sciences.' They never the less held their noses and embraced business instruction because of the tuition revenue that it generated" (McKevitt 217). The creation of the business school marked the Jesuits' concession to the external financial and societal pressures to drift from the Jesuit values of teaching the natural sciences and the humanities to teaching practical matters such as commerce instead. John A. Sobrato's education at the SCU Leavey School of Business is thus a result of an overtime change in Jesuit education and its accomodation to American values. The education Sobrato received was significantly different from that of the very first students at Santa Clara University (then Santa Clara College) and was presumably a completely different form of the education the Jesuits initially desired to provide students at Santa Clara College.

John A. Sobrato's life also shines a light on the journey of Italian women, as his mother had success in real estate even though it was a male-dominated industry, after centuries where Italian "Women were expected to be primarily responsible for household chores and child-rearing, and they often faced discrimination in both the workplace and in education" (Mori). Sobrato's mother no doubt challenged the traditional gender roles of Italian Americans. At the same time, in many ways, Sobrato's mother took on the role of many Italian women throughout Italian-American history. She resembled the clever San Fransisco gold rush wives who made extra money lodging miners as their husbands were out searching for gold, and she resembled the hard-working Italian-American women who worked in factories to support the war effort as their husbands went off to war during World War 2.

A Note about Intersectionality

It is worth noting that John A. Sobrato's story is not just a Catholic or Italian-American story. Sobrato's identity contains intersectionality: He is the son of Italian immigrants, a half-orphan, and a man, and he may belong to other identity groups that we may not even know about, like those with invisible mental health conditions such as depression. Sobrato's status as a billionaire does not solely reflect the plight and triumph of Italian-Americans but also of half-orphans and other identity groups that Sobrato is part of.