Background

Italian Americans entered the 1930s as a prominent immigrant group in the U.S., their communities thriving in cities like New York, Chicago, and San Francisco. With over 5 million Italian immigrants having arrived since the late 19th century, they were among the largest immigrant groups in America (Taylor). However, their rising visibility was accompanied by prejudice. Italians were often stereotyped as uneducated and undesirable, excluded from certain jobs, and targeted for their cultural differences. By the 1920s, pseudo-scientific racism further painted Italians as a “separate race,” amplifying their marginalization (Taylor).

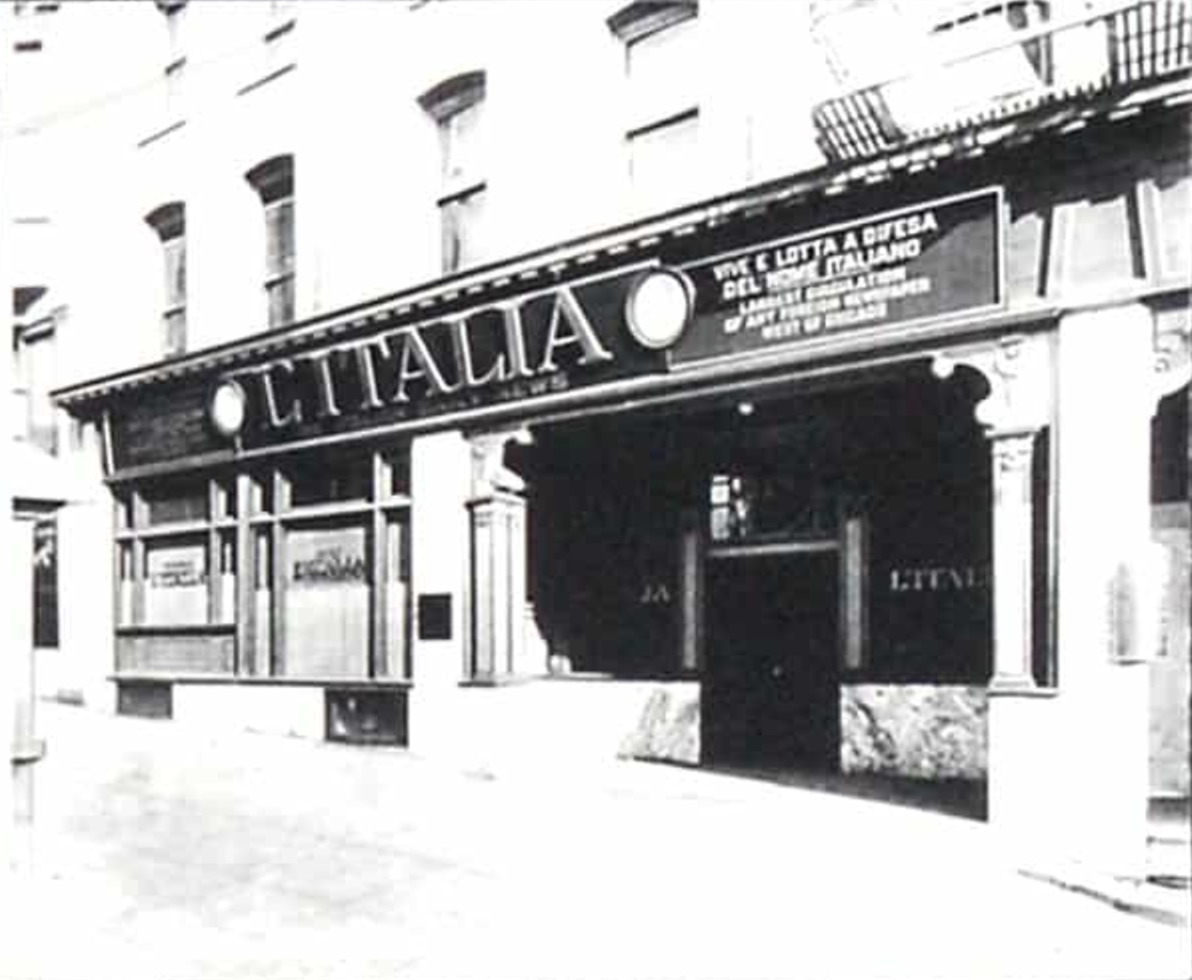

During this era, Benito Mussolini’s rise to power brought renewed pride to Italian Americans, particularly first-generation immigrants. Mussolini’s rhetoric of Italian resurgence and global respect resonated deeply with those who had experienced discrimination in the U.S. Publications like L’Italia, a San Francisco-based newspaper, reinforced these sentiments. The August 1935 edition of L’Italia featured a comparative depiction of colonial holdings, positioning Mussolini’s invasion of Ethiopia as a quest for equity on the world stage (Blakemore). The visual emphasized Italy’s smaller colonial empire compared to Britain, Belgium, and France, framing Mussolini’s actions as both justifiable and necessary.

However, the growing ties between Mussolini’s Fascist regime and Nazi Germany complicated Italian Americans’ loyalties. Second-generation Italian Americans often distanced themselves from overt Fascist support, seeking to integrate into American society. Historian David Taylor notes that this generational divide created tension within Italian American communities, as younger members prioritized assimilation over ethnic solidarity (Taylor). As international tensions escalated, the shadow of Mussolini’s Fascism made it increasingly difficult for Italian Americans to balance their cultural pride with their desire to be seen as loyal Americans.

Contributed by Brian Lee