Contributions to Japan’s Wartime Strategy

The experiments conducted by Unit 731 were intended to advance Japan’s military capabilities by developing biological weapons that could devastate enemy populations and weaken their ability to resist. As Peter Williams and David Wallace explain in Unit 731: Japan's Secret Biological Warfare in World War II, the unit’s research directly informed Japan’s strategy of deploying biological agents in field trials. For instance, plague-infested fleas were released over Chinese villages, causing widespread outbreaks and demonstrating the potential of biological warfare as a weapon of terror (Williams & Wallace, 1989).

These experiments, supported by a comprehensive infrastructure and a philosophy of dehumanization, served Japan’s wartime objectives by advancing knowledge in both offensive and defensive biological warfare. The scale and severity of these atrocities highlight the lengths to which the unit went in pursuit of its goals, leaving a dark legacy of unethical science and human suffering.

The meticulous documentation of these experiments reflects their strategic importance. Every procedure, symptom, and outcome was recorded in detail to contribute to Japan’s biological warfare program.

However, the effectiveness of Unit 731’s work remains a subject of debate. While the experiments yielded a vast amount of data, much of it was scientifically unreliable due to the unethical and uncontrolled conditions under which it was collected. Harris notes that many of the unit’s findings were ultimately of limited utility, undermining their value as a military asset (Harris, 2002). Even so, the data was nonetheless valued by both Japanese authorities and, controversially, post-war U.S. officials who sought to acquire it for their own research purposes. This inefficiency raises questions about the true motivations behind the experiments, suggesting that they may have been driven as much by a desire for power and control as by strategic necessity.

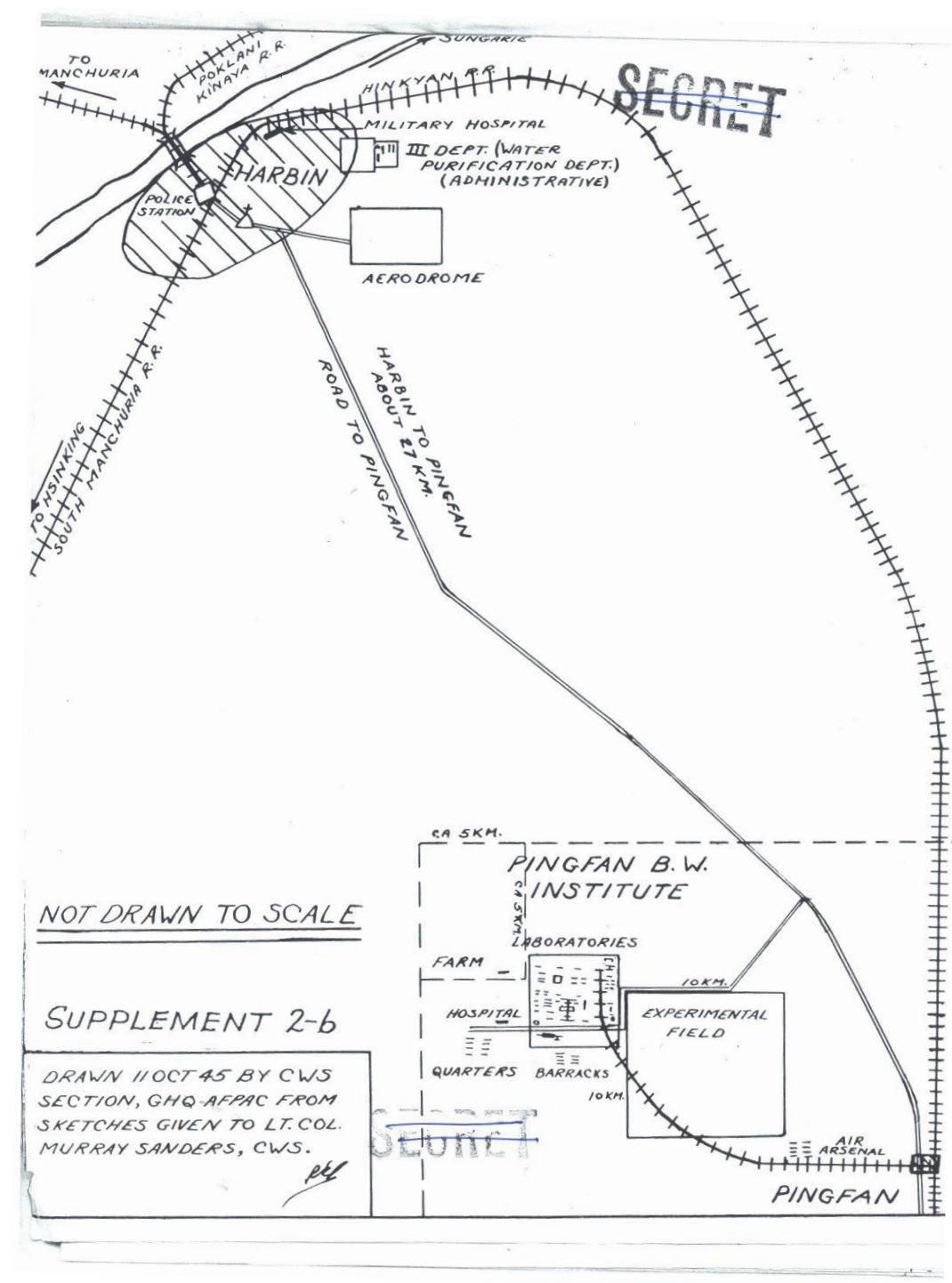

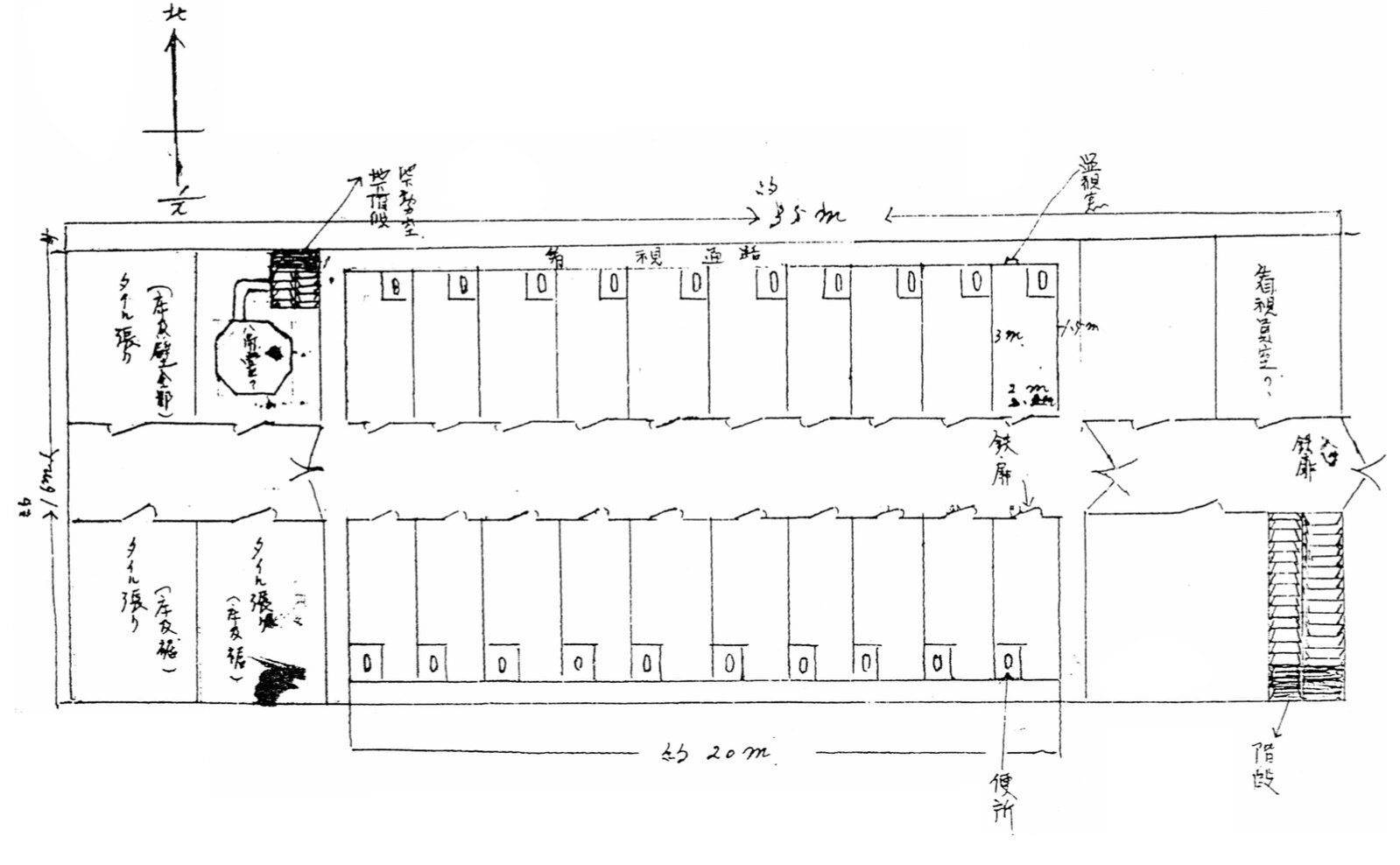

The infrastructure of Unit 731 further underscores the premeditated and systematic nature of its experiments. As illustrated by a 1945 sketch by Sanders and Young (see above), the facilities at Pingfan included laboratories, testing fields, and medical wards that were integrated to support large-scale experimentation. The close proximity between Harbin Military Hospital and the Pingfan BW Institute enabled seamless coordination of medical procedures and biological testing, ensuring that every stage of experimentation could be monitored and optimized.