1980s Propaganda

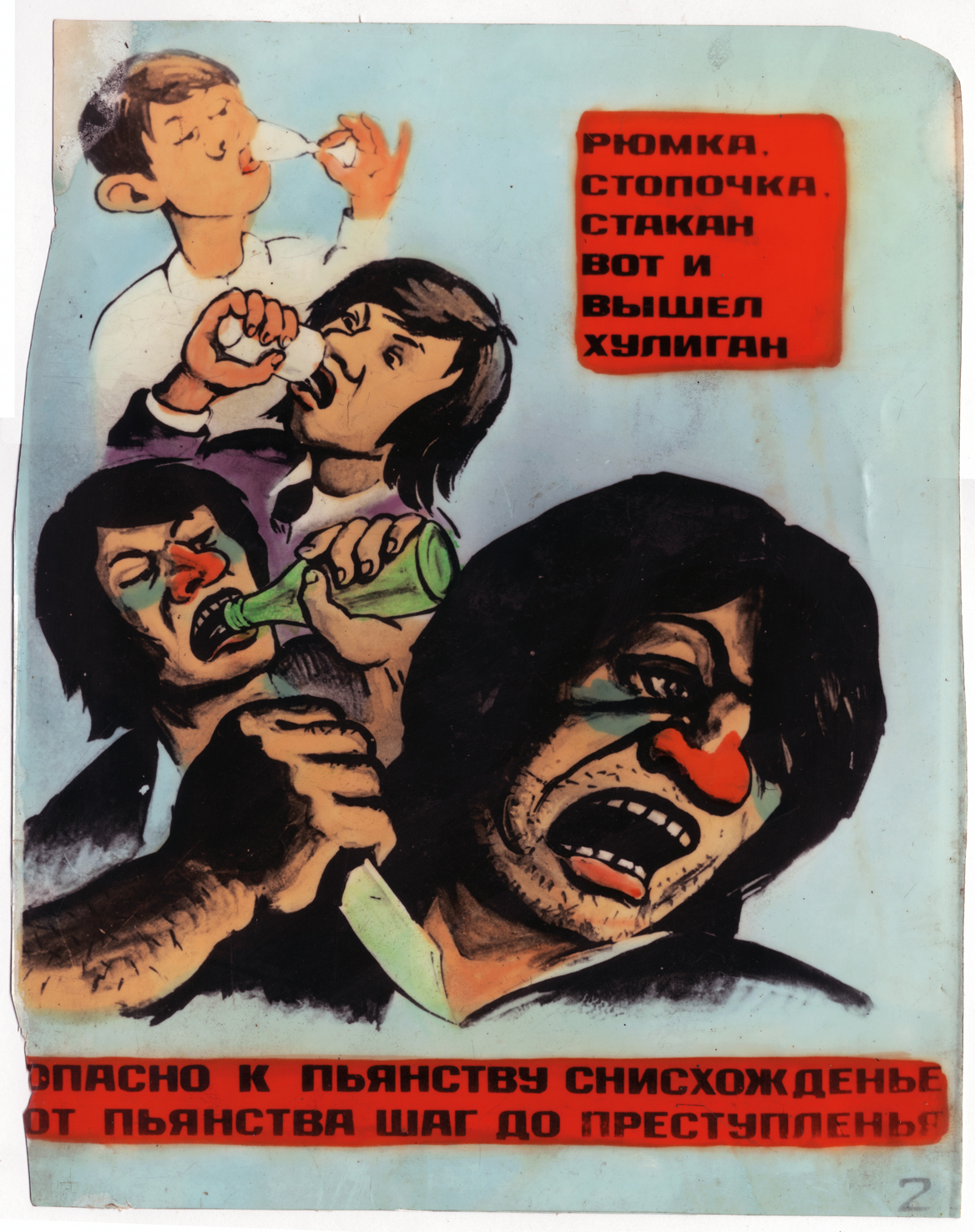

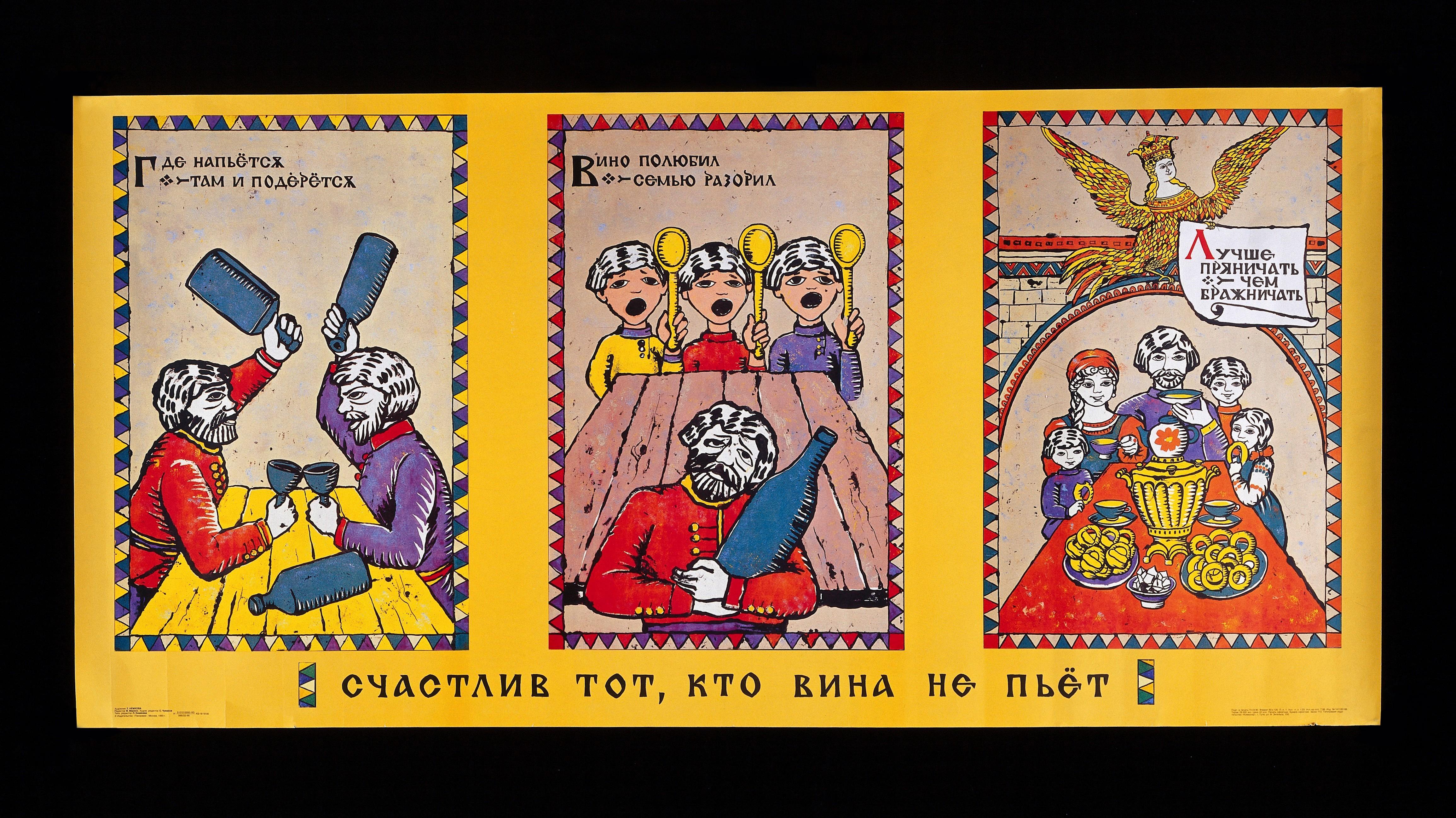

Anti-Alcohol Propaganda

Background

Propaganda in the 1980s reflected an on-going public health crisis: Soviet citizens began consuming alcohol in concerning amounts. The USSR's government officials viewed alcohol (and its abuse) with disgust, expressing impatience, contempt, and anger for those who indulged (Field and Powell 1981, 41). With the turn towards viewing citizens more as individuals, Soviet officials believed that alcoholics had put themselves in that position, and it was their job to get themselves out of it (Field and Powell 1981, 41). Those treated for alcoholism had to either do compulsory work therapy (engaging in social work) or compulsory hospitalization (Field and Powell 1981, 42). The latter was negatively viewed because it was perceived as citizens taking a "paid vacation" instead of seeking help (Field and Powell 1981, 42). All together, citizens felt pressure to be the Ideal Soviet Citizen, but when struggling to achieve this image, they were judged and discriminated for getting help for alcoholism.

The USSR was ranked fourth among 30 countries in the number of alcoholic beverages consumed by someone 15 years and older (Treml 1982, 487). Yet, the majority of the alcohol consumed per person was in the form of a strong beverage, therefore ranking the USSR as the highest in the world for alcohol (Treml 1982, 487). The Soviet Union began to notice this trend, and feared its affect on labor, productivity, and mortality rates.

Gorbachev's Alcohol Policy (1985-1988)

Other leaders of the Soviet Union made attempts to reform and address the issues of alcoholism, but none were as radical or as extreme as what took place in the mid-1980s.

The last President of the Soviet Union, Mikhail Gorbachev, launched sweeping reforms when he took office in 1985, such as glasnost (open government) and perestroika (economic reform). But, included in this agenda was a "moral recovery" focusing on goals such as ending corruption, restoring basic human rights, and ensuring healthy lifestyles for its citizens (Tarschys 1993, 7). Part of this agenda was a "quest for sobriety" due to the growing consumption of alcohol posing health hazards and economic inefficiency/productivity (Tarschys 1993, 7).

Nicknamed the "Mineral-Water Secretary," Gorbachev had a radical stance on alcohol to address the issues stemming from alcoholism (Tarschys 1993, 7). In his first legislation on alcohol in 1985, Gorbachev prohibited alcohol sales in restaurants before 2 PM, set higher prices for wines and spirits, banned liquor from public functions, and reduced the access to commercial outlets that sold alcohol (Tarschys 1993, 8).

This initial legislation sparked the "teetotaller movement" that had 12 million members (Tarschys 1993, 8). All together, the attempt at reducing alcohol consumption was met with some success and approval by its citizens.

With the restrictions on alcohol sales, the Soviet Union lost an estimated 37 billion rubles over the next three years, changing the business cycle and affecting the health of the economy (Tarschys 1993, 10). This demonstrates how important alcohol was to the USSR, and how impactful it was on government revenue.

Effects and Results of Gorbachev's Anti-Alcohol Campaign

These restrictions did not lead to a steep decline in alcohol consumption. Instead, people began to turn towards home production (Tarschys 1993, 8). The number of moonshine producers rose to 397,000 in 1987 (Tarschys 1993, 20).

By 1988, Soviet Union citizens began to complain about the lack of alcohol availability. The government began to allow more oulets to sell alcohol, and to operate for longer hours (Tarschys 1993, 21). The rising production of moonshine was often correlated to increasing crime rates and financial insecurity (Tarschys 1993, 22).

Yet, data demonstrates that Gorbachev's campaign had some success. Sale of alcohol fell*, life expectancy for both females and males increased, fewer people were diagnosed with alcoholism or alcohol-related illnesses, and the number of workplace and traffic accidents and deaths were greatly reduced (Tarschys 1993, 22-23).

*It is important to keep in mind that while sale of alcohol fell, this data does not reflect or include the number of citizens who turned to moonshine production or purchase to get their alcohol fix