1990s Propaganda

Perestroika and Glasnost Reforms

Perestorika (restructuring) and glasnost (openness) were legislation passed in 1985 under Gorbachev that drastically changed the course of the Soviet Union and the led to the end of the Cold War.

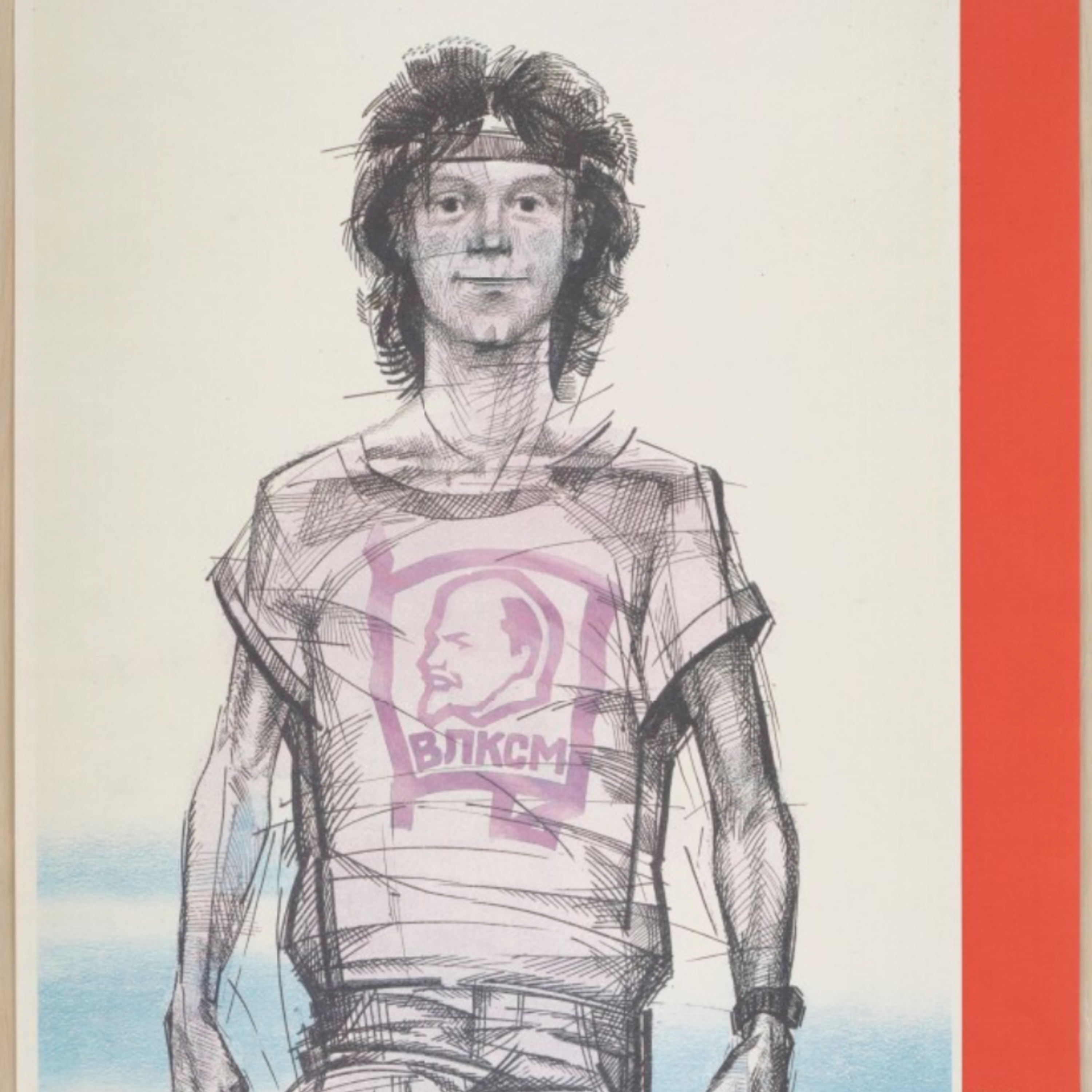

Passed under Mikhail Gorbachev's regime, perestroika was based on Lenin's teachings of socialism, and linked it to democracy (Giadadhubil 1987, 1). The restructuring involved self-financing, full cost-accounting, and independence of management; reform of the small farm economy; introduction of democracy through election of party secretaries; and the condemnation of state suppression through mass media, and harassment of individuals (Giadadhubil 1987, 1). Glasnost championed the liberalization of press freedoms, fine arts, and individual expression.

Soviet Artists Pre-Glasnost

Glasnost was an attempt by Gorbachev to appease citizens who envied the freedoms of Western nations. But, before then, the government was extremely strict about what qualified as art. The government used to only value art if it could be used for propaganda purposes:

"According to the Soviet Constitutional Theory, there are two kinds of opinions: a correct opinion, which is a product of socialist consciousness and encourages the development of a socialist or communist society, and an incorrect opinion, which is of a reactionary nature and hampers social progress. Freedom of speech concerns only the former. The latter is contrary to socialist order and must not be protected" (Berkowitz 1991, 453).

Artists were once separated into two groups. "Official" artists were educated, housed, fed, paid and were part of the state; while "unofficial" artists were targeted by the USSR - sent to psychiatric internment while their art was destroyed (Berkowitz 1991, 454).

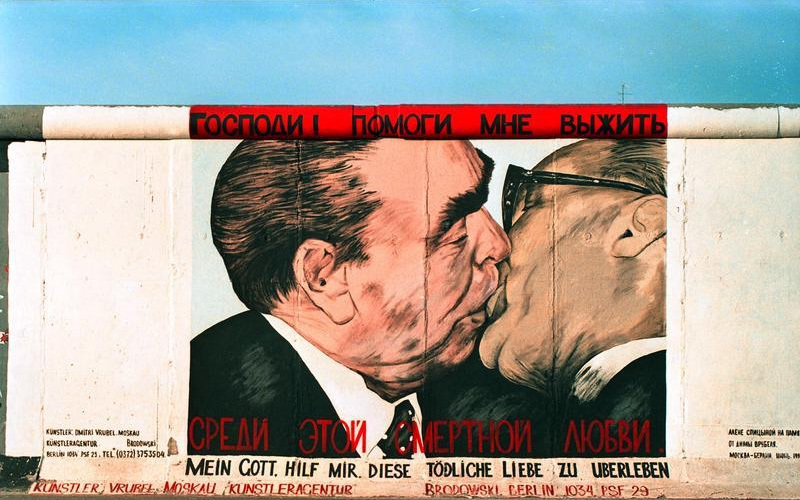

When Gorbachev promised new freedoms under glasnost, the Soviet government changed how it filtered art without codifying these promises into law. As a result, artists feared that their rights were not ensured, and that their expression could still be under threat by the USSR (Berkowitz 1991, 455). They (artists, dancers, journalists, and filmmakers) staged a silent protest in 1990 to voice their fears and frustrations with the Soviet government (Berkowitz 1991, 453). This demonstrates that while the Soviet Union attempted to reform itself and appease its citizens, not everyone felt heard and appreciated by the government.

Soviet Artists Post-Glasnost

The openness of glasnost led to a lot of changes through out the Soviet Union. Films no longer needed to fit a specific ideology, or convey a political message; censorship was used to hide overtly racist, pornographic, or violent films (Berkowitz 1991, 455). The policy of glasnost meant that theaters also changed. For example, roughly 60% of theaters in Moscow in 1990 showed American films (Berkowitz 1991, 459). Rock music was banned, and was once an underground genre. However, glasnost ended the (anti-communist) harassment of rock music. In 1990, an official of the USSR's State Concert Committee hoped that glasnost would lead to the country hosting "two concerts in Moscow with the legendary Rolling Stones" (Berkowitz 1991, 461). Artists and their avant-garde work (theatre, poetry, "bizarre dress") were now marketable to the rest of the western world, turning art into a marketable commodity in the USSR (Berkowitz 1991, 469). The new connection with the west influenced Soviet artists, and vice versa.