Chinese and the Railroad

The contribution of Chinese immigrants to the construction of the Transcontinental Railroad in the mid-19th century is one of the most remarkable chapters in American history. Beginning in the 1860s, thousands of Chinese laborers were recruited to work on the Central Pacific Railroad, which aimed to connect the eastern and western United States. Initially dismissed as unsuitable for such physically demanding work, Chinese immigrants quickly proved to be indispensable. They made up the majority of the workforce for the Central Pacific, with estimates suggesting that over 10,000 Chinese workers were employed at the peak of construction.

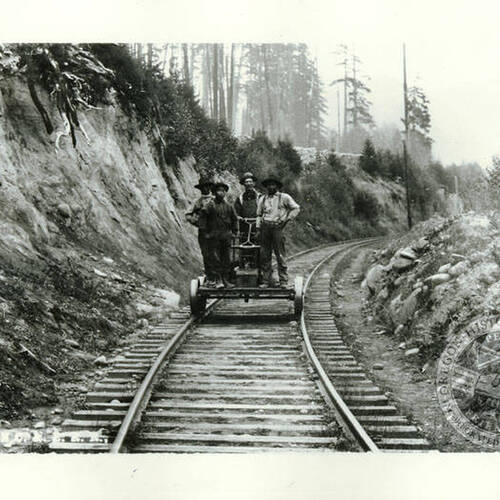

The work was grueling and dangerous. Chinese laborers faced harsh conditions, particularly when laying tracks through the rugged Sierra Nevada mountains. They worked tirelessly to blast tunnels through solid granite, often using dynamite, which posed extreme risks to their safety. The winters were brutal, with snowstorms burying camps and workers under feet of snow, while summers brought relentless heat. Despite these challenges, Chinese workers persevered, demonstrating remarkable discipline, resilience, and ingenuity. They developed innovative methods to complete tasks, such as using bamboo baskets to lower workers down cliffs to drill holes for explosives.

Chinese laborers were paid significantly less than their white counterparts—often just $30 to $35 a month—and had to provide their own food and lodging. In addition to low wages, they endured discrimination and social isolation. Yet, their contributions were vital to the project's completion. On May 10, 1869, the Transcontinental Railroad was finished with the ceremonial driving of the "Golden Spike" at Promontory Summit, Utah. (Figure 1) However, Chinese workers were notably excluded from the celebration, a poignant reflection of the systemic racism they faced.

The completion of the railroad transformed the United States, facilitating commerce, westward expansion, and the movement of goods and people across the country. For Chinese workers, though, the end of the project often marked the beginning of new struggles. Many were left unemployed and continued to face widespread discrimination, including violence and exclusionary laws. Despite these hardships, their labor remains a cornerstone of America's infrastructure and progress, and their legacy is a testament to perseverance in the face of adversity. Today, monuments and historical recognition honor the sacrifices and achievements of these Chinese pioneers, ensuring their stories are remembered as an integral part of American history.