Common Parental Expectations vs Common Characteristics

This podcast is referenced throughout this page with timestamps to listen to for each of the various sub-topics.

Education

Children of Indian immigrants often face substantial expectations to excel academically and professionally. Since many Indian immigrant families include professionals who moved to the U.S. seeking better opportunities, education is highly valued as a pathway to success. Second and third-generations of Indian Americans are typically encouraged to pursue higher education, with a college degree seen as a baseline requirement. Careers in fields such as medicine, engineering, and business are considered secure and prestigious. Meanwhile, pursuits in the arts, humanities, or social sciences are often discouraged due to their perceived lack of financial stability. However, attitudes toward these alternative fields are gradually shifting and parental attitudes toward education vary from family to family.

In many families, Indian American students excel in their academic environments due to a strong work ethic and family-oriented values instilled from an early age. Despite these achievements, the intense pressure to succeed can negatively impact the kids who perform at an average level or struggle academically. This pressure can lead to feelings of failure or inadequacy, particularly in a community where seeking mental health support has been traditionally viewed with stigma (Pavri, Gale Encyclopedia of Multicultural America, Section on Asian Indians).

The “model minority” stereotype surrounding Indian American youth further amplifies these challenges. While the stereotype highlights academic and professional accomplishments, it also imposes unrealistic expectations and ignores individuality. Not all Indian American children adopt the same drive for achievement as their parents, and those who do not meet such high standards can feel as though they are falling short, even when their performance aligns with broader societal norms in the United States (Segal, The Indian American Family).

The dynamic between generations can sometimes create tension. While parents value traditional expectations, such as compliance and achievement, their children, immersed in a more individualistic American culture, may desire greater autonomy. This generational gap often plays out in career decisions, as children strive to balance parental expectations with their own aspirations.

College can be a transformative experience for Indian American youth, providing a space to explore identity and build community. For some, it becomes a place to find "their tribe" and reconnect with their Indian heritage. By participating in cultural organizations and meeting peers with similar backgrounds, they may feel “more Indian” than they did at home, where the pressures of academic and career success dominate (Verma, Namasté America: Indian Immigrants in an American Metropolis).

Listen to DesiAmericanLife Podcast from 7:36-7:48

Language

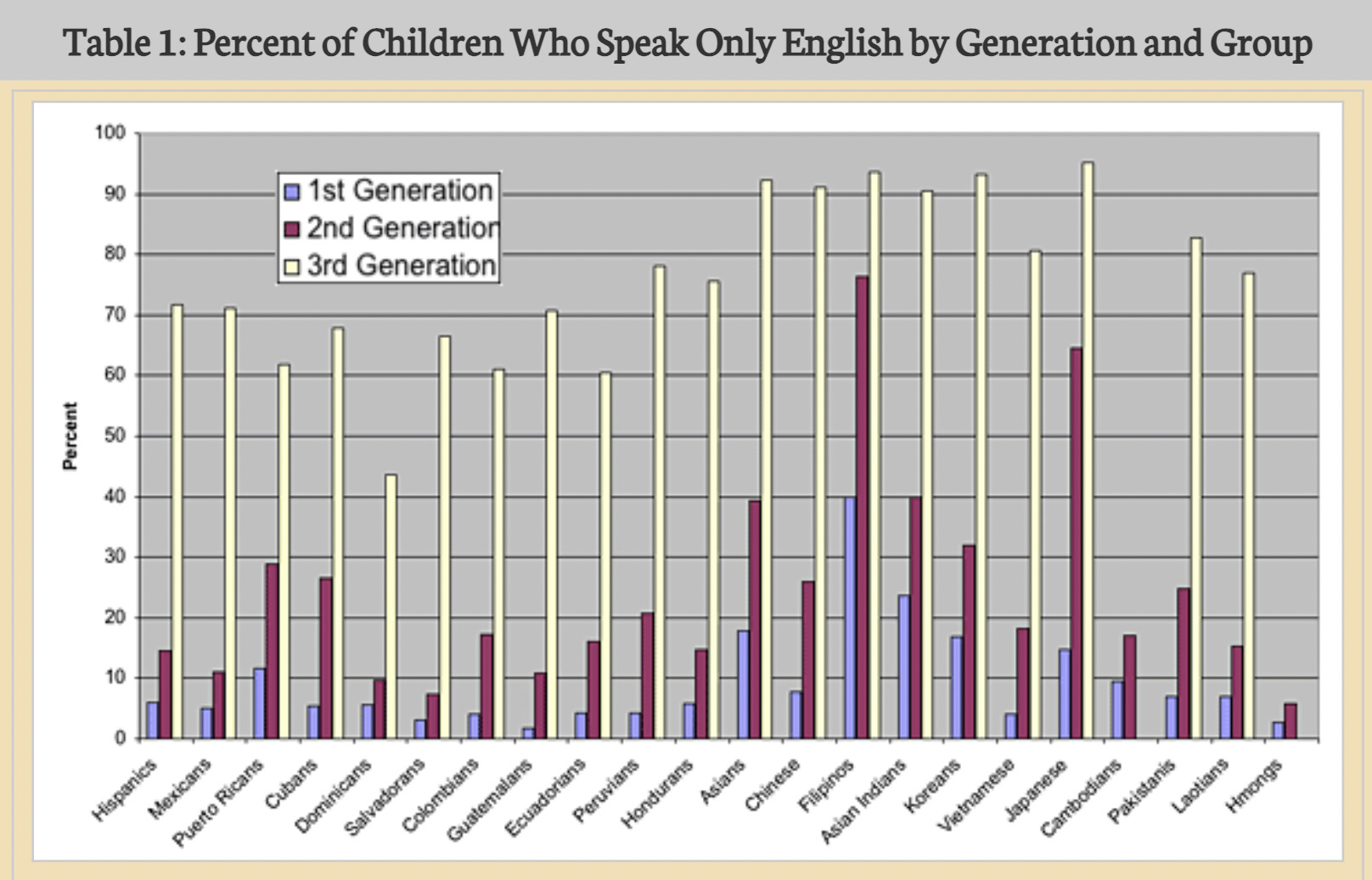

As can be seen by the table above, Second and Third-generation Indian Americans who only speak English are standard within the U.S. While Second-Generation children often grow up bilingual, speaking an Indian language at home and English outside, fluency in their parents’ native language diminishes significantly over time. By the Third Generation, English becomes the primary and often the only language spoken at home.

This is a stark contrast to the First-Generation of Indian Americans who were more likely to speak at least two languages, English and Hindu, in addition to the language(s) commonly spoken in their home state in India.

Motivated by cultural pride and desire for cultural preservation, parents of Second-Generation Indian American children commonly strive to pass on their linguistic ties. However, they face various challenges while attempting this.

In large part, this is due to English being the main spoken language within the U.S. Because the youth are in predominantly English-speaking environments such as schools, and society at large, there are limited opportunities to use their ancestral language outside the home. Even among fellow Indian Americans, English tends to dominate conversations. This is because there are so many different Indian languages that the children might speak, so English is usually a common ground for everyone. Parental efforts to enforce language use may be in place at home such as creating rules to speak only in a specific Indian language. Or it could be through enrollment at a linguistic school such as the popular Hindu summer camps. But again, these efforts are manytimes undermined by the broader English-speaking environment. Additionally, practical considerations play a role. Not every First-Generation parent decides that teaching their children their ancestral language is their top priority. For some, they might see the lack of practicability within American culture as little incentive to pass on the languages they know (Verma, Namasté America: Indian Immigrants in an American Metropolis).

Usually by the Third Generation, the connection to ancestral languages is very weak due to all the reasons listed above: minimal exposure and declining practical relevance. Children of this generation are typically monolingual, speaking only English. Their interest in learning Indian languages is often overshadowed by the cultural dominance of English in the U.S.

Listen to DesiAmericanLife Podcast from 10:56-12:04

Religion

The image to the left depicts a celebration of an Indian American family's Christmas. This could represent an Americanized blend of tradition and religion. Alternatively, this family might have originally been Christian and would've celebrated Christmas regardless of their geographic location, as the limited information makes it difficult to determine.

The Indian American community is highly diverse in religious practices, reflecting a wide variety of traditions and approaches to preserving heritage. Many families blend these traditions with American cultural influences and resources, creating unique ways of carrying forward their faith and cultural identity.

Listen to DesiAmericanLife Podcast from 12:05-12:49

Food

Food can vary dramatically from family to family. For many, the expectation is that traditional Indian food is eaten during important holidays such as biryani, samosas, or mithai, which serve as a connection to cultural heritage. Additionally, food preferences and dietary restrictions may be influenced by the religious identity of the First-Generation. In some families, meals will often blend traditional Indian flavors with American cuisine. Usually, the matter of food is not a huge issue between generations. Both parental expectations and food habits reflect a mix of preserving tradition and adapting to American culture, with each generation and family finding its own balance between the two.

Relatives

Many families who can afford it will take their children, the Second and Third-Generations of Indian Americans, back to India to connect with their relatives and friends. Often-times this is done annually but depending on the individual family and a variety of other factors, these visits may be limited for more special occasions such as weddings or funerals (Verma, Namasté America: Indian Immigrants in an American Metropolis).

Some families have their extended family living in the U.S. as a result of chain migration which tends to make for a stronger community and support system for the Second and Third Generations.

Listen to DesiAmericanLife Podcast from 6:41-7:32

Parenting

Pictured above is an Indian American family with the First-Generation Indian American immigrant parents, and their Second-Generation Indian American children.

Parental expectations versus the desires of the youth don't always align. Despite conflicts that might arise because of this between generations within families, the inherent strengths of Indian family dynamics often provide strong support for children during crucial periods. Many of the youth, even when facing parental control and communication struggles, feel securely grounded in core human values due to the guidance and training provided by their parents. These children often have a deep confidence that their familial ties are stable and lasting.

When these Second Generation children grow up and become parents themselves, they are often more sympathetic to Westernized practices their children have and they often are more knowledgable with regards to balancing cultures having experienced this themselves (Segal, The Indian American Family).

Listen to DesiAmericanLife Podcast from 30:15-31:22

Dating and Marriage

"And we are very happy Charu met somebody...who is not from India. And who cares a lot for her and they’re married. So we’re happy with that... I would be lying if I said initially that, um, I encouraged her to see if she could find somebody who was of Indian origin. Or their parents were from India. I honestly yes, I may have discouraged it, initially. But, once she had decided, we were both 100 % with her." - Santosh Wahi Interview

The sentiment above as expressed by Santosh Wahi, a First-Generation Indian American is a common one in which parents tend to wish for their children to marry within the Indian community because they are desirious of maintaining the cultural ties. However as can be implied by Wahi's quote, most parents just want their kids to be happy and though they might prefer an Indian marriage match, support their children no matter the outcome.

While many Indian parents still prefer their children to marry within their community, they are increasingly accepting of their children's choices, especially as intermarriages with non-Indians rise. This shift is not terribly surprising given the constant interaction second-generation children have with non-Indians (Segal, The Indian American Family).

The topic of dating is a contentious issue in some Indian American families. While Second-Generation children are accustomed to American values of personal choice, many First-Generation parents worry about mixed marriages and cultural erosion. Despite differences in perspective, a lot of Indian parents try to accommodate their children's views, leading to ambivalence toward dating and marriage.

Although dating is not a traditional practice in Indian culture, parents are gradually allowing it. However, there remains a strong preference for arranging marriages within the community, with parental approval and involvement in the selection process. Parents prioritize partners who share similar cultural, religious, and social backgrounds, believing that such unions are more likely to result in stable, lasting marriages and ensure the continuation of their cultural values (Verma, Namasté America: Indian Immigrants in an American Metropolis).

Listen to DesiAmericanLife Podcast from 32:40-35:15

Listen to DesiAmericanLife Podcast from 37:02-40:13

Gender Roles

Gender roles within Indian families can vary, but many cultural expectations around gender persist both in India and the U.S. Often, families will encourage women to pursue higher education, but not always for personal independence. Sometimes, this encouragment is done to improve marriage prospects and boost the family’s social status among the Indian community. Even when employed, many women feel pressure to prioritize family duties over their careers. However, more Second and Third Generation Indian American women are now prioritizing professional careers and making independent life choices (Segal, The Indian American Family).

As previously mentioned, another shift has been in the domestic gender roles as Indian men are commonly taking on more childcare and household responsibilities, adapting to the needs of their environment and modern influences.

Cultural education is also shaped by gender expectations. Girls are often encouraged to take lessons in dance, music, and singing to preserve traditional practices, while boys are typically not expected to engage in these activities, though some may be encouraged to learn to play Indian instruments (Verma, Namasté America: Indian Immigrants in an American Metropolis).

Listen to DesiAmericanLife Podcast from 29:01-29:52

Personal Narratives of Second and Third-Generation Indian American Identities

As formerly mentioned, everyone has a different outlook and experience when it comes to their identity. Some individuals from the Second and Third generations of Indian Americans may feel pressured to define their identity, questioning who they are, where they come from, and how they see themselves. Many young people challenge the very need for this identity labeling, fearing that embracing an Indian identity might be seen as rejecting their American identity, or vice versa.

Depending on their experiences or circumstances, they may draw from an Indian or American influence, or a mixture of both. Regardless, all of which are equally legitimate. Featured below are different people's perspectives and stories, which are meant to be examples for the diverse ways in which individuals have navigated their cultural and personal identities and grappled with being Indian American.