Common Characteristics

Education

"[T]he immigrants that I see from India are different. They came with enough knowledge and education to rely on. And it wasn’t that if they went back to India they would be tortured or anything. Or it wasn’t that we couldn’t support ourselves back in India. Perhaps we couldn’t have lived the same standard of life that we lived here, but we would’ve lived the same standard life that we were used to prior to coming here. So our immigrating is different. We had a choice and we still have a choice." - Shanta Gangolli Interview

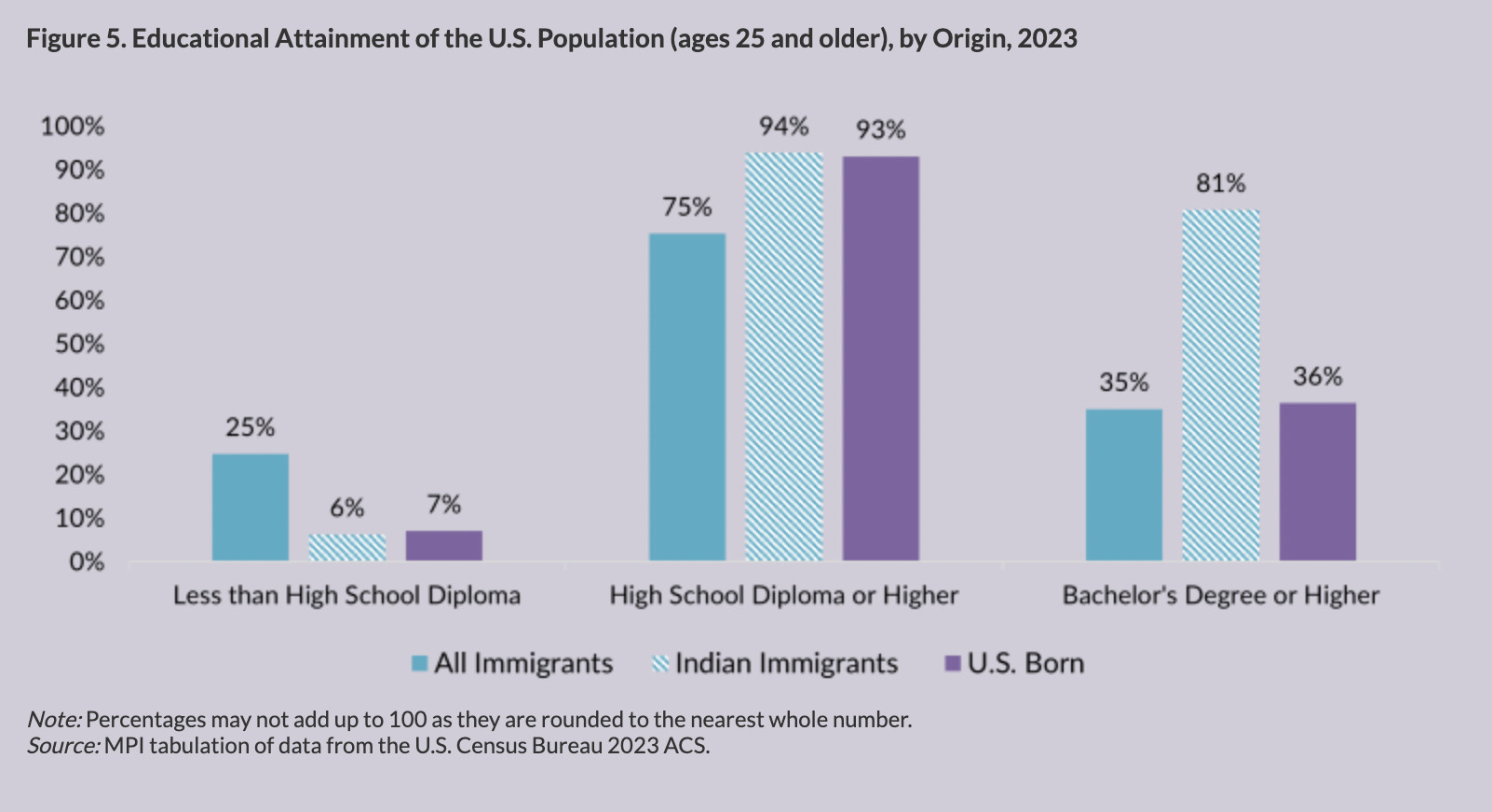

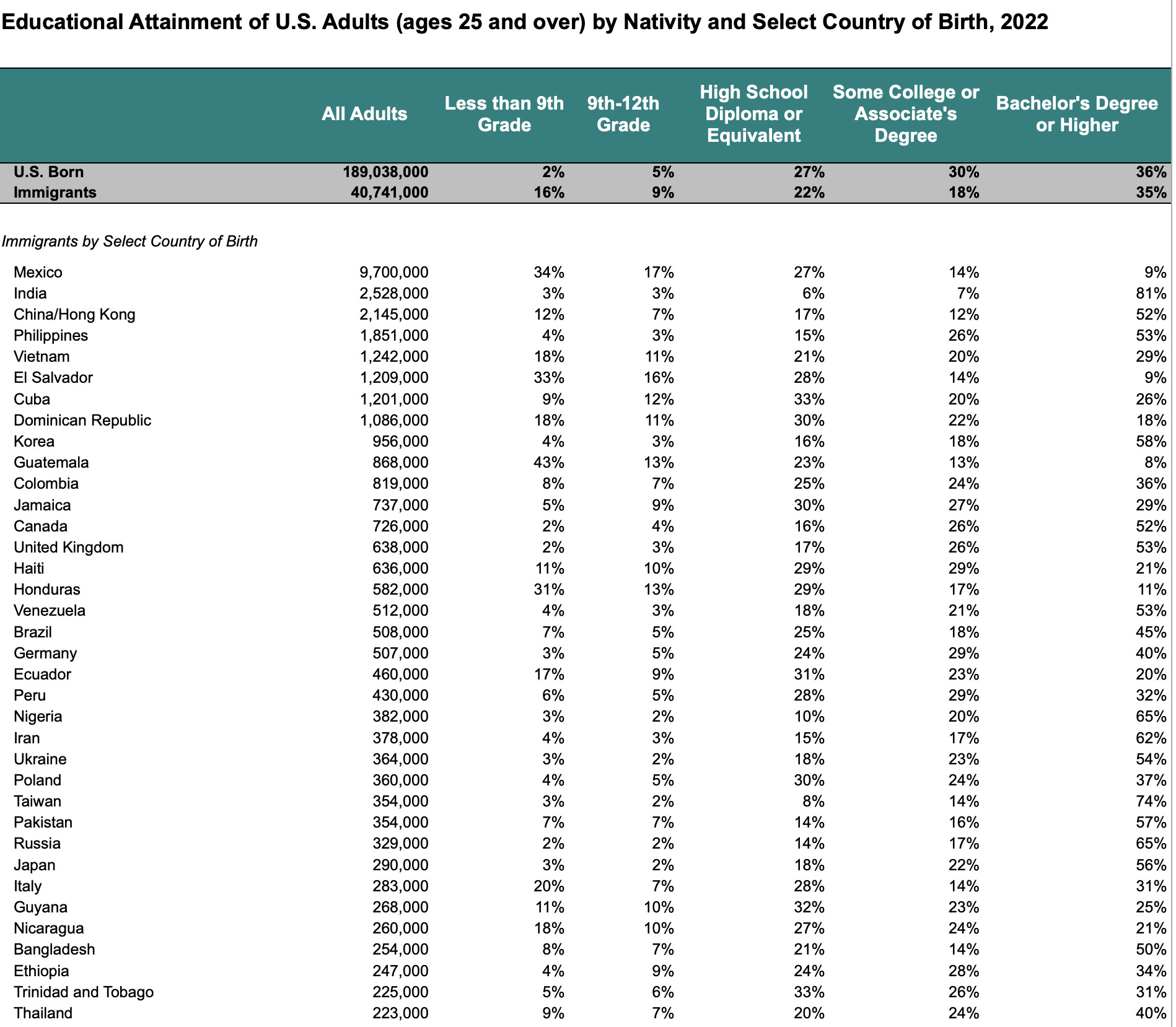

In general, Indian American Immigrants tend to have a higher educational background than the majority of U.S. immigrants. This can be seen by Fig. 1, a bar graph of the data from Fig. 2 which has the data in table format. The figures display the percentages of students from India who were enrolled in U.S. higher education institutions during the 2022-23 school year as compared to the percentages of all immigrants, as well as U.S. born students, who were enrolled in U.S. higher education insitutions during the 2022-23 school year. In 2023, 81 percent of Indian immigrants ages 25 and older reported having at least a bachelor’s degree, compared to 35 percent of all foreign-born and 36 percent of U.S.-born adults. Indians are also much more likely to hold graduate or professional degrees: 49 percent of Indian immigrants held an advanced degree in 2023, versus 16 percent of the total foreign-born and 14 percent of the U.S.-born populations.

First-Generation Indian American immigrants are usually keenly aware of the value of a U.S. education, and whenever possible, go on to acquire an American degree. However, this is not always the case as there are many First-Generation Indian Americans who exist on the margins of U.S. society and haven't had the same education or ability to pursue education within the U.S. Also, somtimes the extended kin of the First-Generation immigrants, such as their brothers or sisters, were much less educated and were able to come to the U.S. because of the Family Reuinification preference. The stereotype of Asians as the "model minority," along with these educational statistics in Figures 1 and 2, can mask inequalities and within the community. So, it feels important to note that despite the typically strong emphasis of education within Indian culture, not everyone shares these educational experiences (Deepak, Parenting and the Process of Migration: Possibilities Within South Asian Families).

Language

India's linguistic diversity, with over 300 dialects and 24 spoken by more than a million people, is mirrored within the Indian community in the United States. First-Generation Indian immigrants often maintain their native languages at home, communicating with spouses, extended family, and community members. Many are also fluent in English, one of India’s two official languages (the other being Hindi), which has eased their integration into American society (Pavri, Gale Encyclopedia of Multicultural America : Asian Indian Americans).

Regional and linguistic differences play a significant role in shaping Indian American identity. In India, these diverse groups have historically fought to preserve their languages and cultures, a determination they carry with them to the U.S., where retaining a linguistic identity helps maintain connections to their homeland. At the same time, the widespread use of English has fostered a broader Indian American identity, uniting individuals across linguistic divides (Verma, Namasté America: Indian Immigrants in an American Metropolis).

Religion

By the 1990s, First-Generation Indian Americans had established temples and religious institutions, creating a foundation for the Second Generation to build upon. Religion has been a key way for Indian Americans to maintain cultural continuity, with practices varying based on religious affiliation, regional background, time spent in the U.S., and personal beliefs. While many Indian Americans tend to celebrate traditional holidays like Diwali, even if they are not particularly religious, many will also participate in American religious and social events. This blending of Indian and American influences reflects the diversity of religious practices within the Indian American community (Verma, Namasté America: Indian Immigrants in an American Metropolis).

Food

Most First-Generation Indian Americans followed diets centered around traditional Indian food, which features a wide array of spices such as cumin, turmeric, chili powder, ginger, and garlic. Their meals commonly included various dishes made with lentils, beans, and rice. Dietary preferences were usually influenced by religion.

Initially, options for Indian goods and services in the U.S. were scarce. However, the arrival of second-wave Indian American First-Generation immigrants led to the establishment of Indian grocery stores, restaurants, and banquet halls in urban areas. One example pictured below is the Patel Brothers grocery store, founded by the Patel family in the 1970s. Over time, Patel Brothers have grown into a highly successful supermarket chain, providing easy access to authentic South Asian ingredients and spices for traditional Indian cuisine to people across the nation. The store represents a blend of practicality and cultural preservation, creating a space for cultural exchange while staying rooted in its Indian heritage (Verma, Namasté America: Indian Immigrants in an American Metropolis).

Relatives

Many First-Generation Indian Americans who were financially able, made annual trips to India to visit family and attend significant events such as weddings. Chain migration, enabled by the 1965 Immigration and Nationality Act, also significantly shaped family dynamics. Indian American residents had the option to sponsor family members, such as parents, elderly relatives, and siblings, to join them in the U.S. For those that chose to immigrate through family reunification means, this created extended networks of relatives. Bringing over relatives was one way for First-Generation immigrants to transplant more of the world of origin. However, this was a costly and time-consuming process, on top of the fact that many of these extended family members chose to stay in India.

In India, extended families living together was common, but in the U.S., the nuclear family was and remains the predominant and socially accepted household structure. However, there is no "standard" Indian household, as Indian society encompasses a wide variety of family arrangements. This cultural flexibility allowed for Indian families to adapt to alternative household structures when business or family needs required it (Verma, Namasté America: Indian Immigrants in an American Metropolis).

Parenting

Listen from 1:14-1:48

This segment of the podcast delves into the universal challenges of parenting in general, and goes on to mention the unique struggles of balancing the dual identities of raising children as both Indian and American. As a result, various groups and subgroups within the Indian community in the United States have emerged, organized around language, regional background, culture, and religion. These groups aim to pass their values on to the second generation.

"And my mom, as a mom, if I compare her to me, to myself, in that situation. Certainly, she had us. She had four of us. But then she had a lot of help. And not to minimize her responsibilities; certainly, she had a lot of responsibilities, to care and see that everything was just right. I think it was different in that sense. Yes, we had the children all to ourselves. Whatever was to be done for them was done by us." - Santosh Wahi Interview

This quote, reflects the fact that many First Generation Indian American parents lacked the extensive support systems they were accustomed to in India. Instead, their community often consisted of other young Indian couples or close friends in their neighborhood, as many extended family members remained in India. This limited network added another layer of complexity and difficulty to parenting in a new cultural context for First Generation Indian American immigrants.

Marriage

Many First-Generation Indian immigrants commonly married within their ethnic group. Additionally, arranged marriages or introductions from parents were popular as this practice was alive and widespread in India. Sometimes, these immigrants would come to the United States with their significant others, whereas others went home to find a significant other and get married.

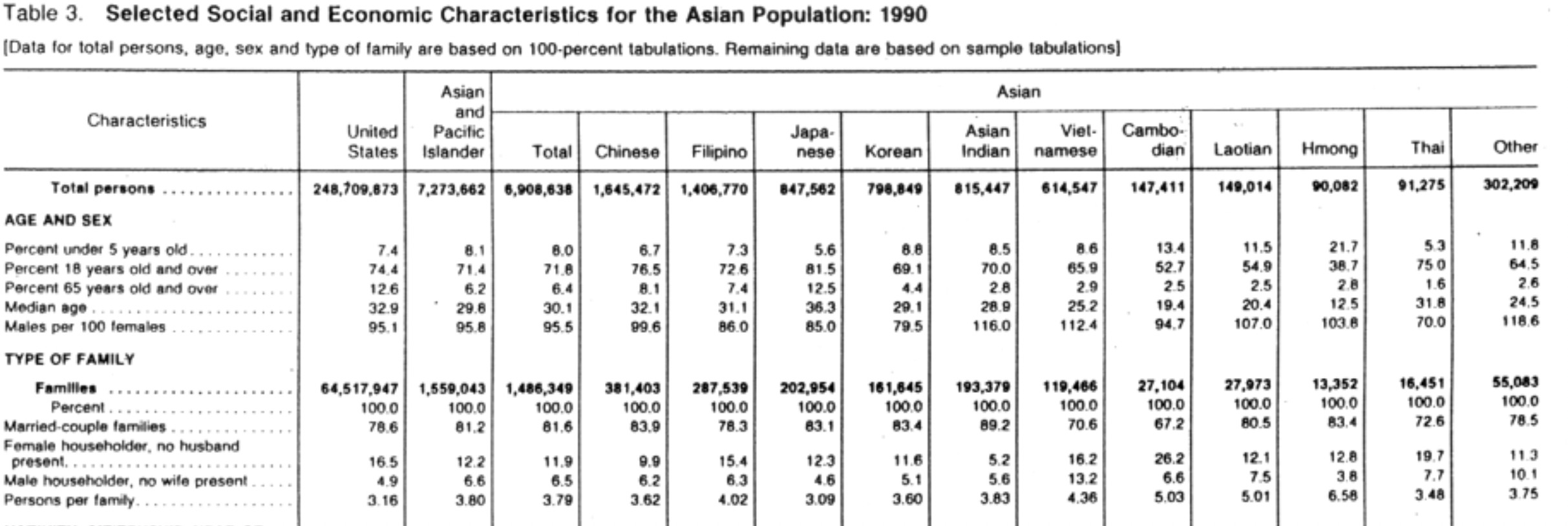

As shown in Fig. 3: 89.2% of Indian American immigrants were "married couple" families. This was higher than any other Asian group in 1990. Additionally, the average family size at this time was 3.8 person per household.

Gender Roles

"But you know, in the last ten years, the young people would have panel discussion – you know, growing up in two cultures. These were the Indians’ children. And at one time, I got very sick of it. I said, 'Have you thought of the women who came from India, like me and your mothers, who had to adjust to the life here?' Become an American mom, drive kids around to all the activities, participate in PTAs, do the housework, which she was not used to. Have no help from the husbands because the husbands were not used to helping. Learn driving, which they never did [before]; if they could afford a car in India, they would have a driver. They had to adjust more to the lives here, having been brought up in India and then adjusting to their children’s needs. And then the children, the question of dating, drugs. The mothers have gone through more problems than these children who constantly used to have these panel discussions about being brought up in two cultures. It was hard for them, true, but I think it was hard for the mothers also – more than the father, because father was busy with his work and was still not used to being an American father. Whereas mothers had to take the role of an American mother, learn driving, do all the chores that an American woman does, which she never did before. In the house, outside, do lawn, get the gardening if they had a house. Entertain. And then attend to the children’s activities, you know." - Shanta Gangolli Interview

Indian women were often working in addition to being the traditional homemaker and caregiver to children. Pursuing some sort of higher education or working while taking primary care of children was seen as normal. There was an uneven balance of responsibilities that led to growing pushback and changing gender roles and expectations for Indian men and women. Men were increasingly expected to become a more active part of raising children and helping with household duties. Many First-Generation Indian immigrant women found themselves navigating dual roles, balancing their identities as both wives and workers.

Hierarchy has traditionally been a key feature of family life in India, with authority typically determined by gender and age. In this structure, parental authority is paramount, requiring women to be deferential wives but allowing them to take on authoritative roles as mothers. Some First-Generation Indian American families adhered to these traditional gender roles, but typically, immigration to the U.S. brought significant shifts in responsibilities and expectations for both men and women.

Indian women in the U.S. faced new cultural and community responsibilities. They became key figures in maintaining and transmitting Indian culture, particularly within religious and ethnic institutions, which often emphasized traditional roles of women as housewives and family caretakers. This expectation of subsuming individual identities for the greater good of the family created a tension for working women, as it clashed with their lived experiences and evolving identities (Bhalla, Couch Potatoes and Super-Women).

To Read More: "Couch Potatoes and Super-Women": Gender, Migration, and the Emerging Discourse on Housework among Asian Indian Immigrants