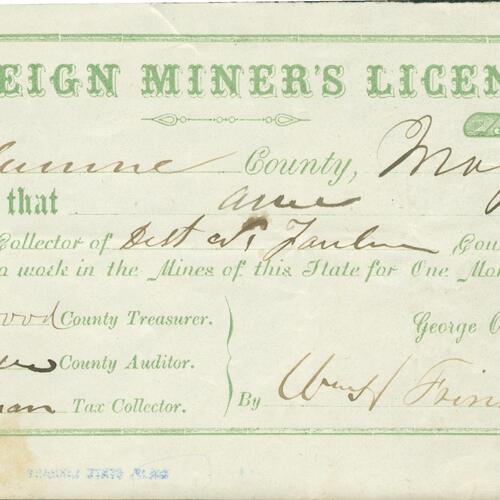

Foreign Miners' Tax Act

The Foreign Miners’ Tax Act of 1850 was a discriminatory law passed in California that imposed a monthly fee of $20 on foreign miners, targeting Chinese and Latin American workers. While repealed briefly in 1851, it was reintroduced in 1852 with a lower fee of $4. This law financially burdened Chinese miners, forcing many to abandon their claims and seek work in other industries. It entrenched economic discrimination, drove the formation of Chinatowns as refuges, and set a precedent for future exclusionary policies like the Chinese Exclusion Act. Despite these hardships, Chinese immigrants displayed remarkable resilience, forming organizations to advocate for their rights and adapt to their hostile environment. The tax not only reflected the racism of the era but also fueled the systemic marginalization of Chinese communities in the United States.